“…

Write, he had said. I must write – I must, indeed! I shall write – never fear.

Certainly. That’s why I am here. And for the future I shall have something to

write about.”

He was exciting himself by this

mental soliloquy. But the idea of writing evoked the thought of a place to

write in, of shelter, or privacy, and naturally of his lodgings, mingled with a

distaste for the necessary exertion of getting there, with a mistrust as of

some hostile influence awaiting him within those odious four walls.

“Suppose one of these

revolutionists,” he asked himself, “were to take a fancy to call on me while I

am writing?” The mere prospect of such an interruption made him shudder. […] “I

wish I were in the middle of some field miles away from everywhere,” he thought.

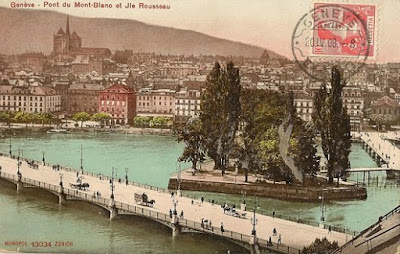

He had unconsciously turned to the

left once more and now was aware of being on a bridge again. This one was much

narrower than the other, and instead of being straight, made a sort of elbow or

angle. At the point of that angle a short arm joined it to a hexagonal islet

with a soil of gravel and its shores faced with dressed stone, a perfection of

puerile neatness. A couple of tall poplars and a few other trees stood grouped

on the clean, dark gravel, and under them a few garden benches and a bronze effigy

of Jean Jacques Rousseau seated on its pedestal. […] He had found precisely

what he needed. If solitude could ever be secured in the open air in the middle

of a town, he would have it there on this absurd island, together with the

faculty of watching the only approach.”

I was running late when I caught my

train from Martigny. The journey to Geneva, with some very beautiful views for

most of the way along the coast of Lake Leman, would take almost 2 hours. As

the train pulled out of the station I worked out that I had two possible

options. I could get off the train one stop early and attempt to make my way

there on foot. Or I could go straight to the airport and leave my bag in the

left luggage whilst I made a dash into town and back in a taxi. As I didn’t

know the streets of Geneva, and I had no map of the place with me, I decided to

hang the expense and go with option two. Trundling a suitcase blind through

bustling streets, navigating purely by luck and vague inklings didn’t seem the

sensible choice given that I had a flight to catch. Besides, there seemed

something wholly appropriate about hurriedly stuffing my suitcase into a coin

operated locker at the airport and then hailing a taxi.

“Where to?” the

taxi driver asked, in French.

“ Île Rousseau, s’il

vous plait,” I replied.

In my mind, I

like to imagine the taxi pulling away and me casting a glance out of the back

window, just to check I wasn’t being shadowed. But in reality the taxi driver

wasn’t Swiss and had to get out a map for me to point out where I wanted to go.

He seemed a little bemused.

“Tourist?”

“Oui” – Non! ... Je suis une spy!! ... Allez, Île Rousseau – Tout suite!

To be fair

though, the taxi ride did feel a little like a chase scene in a spy movie as it

was pretty much a swift almost straight descent through the streets of Geneva

to the lake front. And as the taxi pulled round into a little street

overlooking the water I looked out of the window to see I was about to step out

of the car at the entrance to a very plush hotel. I paid the driver and he very helpfully

explained where to go to find a taxi rank to get back to the airport.

“Merci beacoup.”

I got out of the

taxi and the hotel doormen looked momentarily bemused.

“Bonjour,” I

hailed them with a big smile and then, as the taxi sped away, I turned and walked

purposefully in the other direction.

Crossing the street I could see the

little island ahead of me. It wasn’t at all how I’d imagined it, although it

fitted the description in Joseph Conrad’s novel exactly. Two angled foot

bridges meet in the middle of the river channel and at the apex a short bridge

lead across to the tiny little island. Just as Conrad describes, its sides are made

of dressed stone, there are a few tall trees under which are some benches, the

ground is mostly gravel, and there is a refreshment kiosk. A road bridge passes

close by on the far side of the island, beyond which stretches the vast expanse

of the lake. The only things which seem to be different were the modern modes

of conveyance zipping noisily across the road bridge in each direction, and, of

course, the enormous jet of water spouting out of the lake, which an hour or so

later I could clearly see out of my aeroplane’s window as I soared into the

clear blue sky. The bustle of people on the island was perhaps a contrast

to the scene in the book too. I doubt Mr Razumov would get the peace enough to

scribble his secret notes there today, although I could well imagine two spies

making a secret rendezvous here, strolling about and talking in hushed tones,

their conversation masked by the rushing sound of the wind passing through the

leaves of the tall Italian poplars and the weeping willows.

As I’d sat on the train, watching

the shimmering blue of the lake and the white misty wall of mountains on the

far shore passing by, I’d been reminded of another passage in a different book

which I’d also read along time ago. This one was by Jean Jacques Rousseau

himself. It was the distant sight of a boat across the water which had prompted

its recall.

“My

morning exercise and its attendant good humour made it very pleasant to take a

rest at dinner-time, but when the meal went on too long and fine weather called

me, I could not wait till the others had finished, and leaving them at table I

would make my escape and install myself alone in a boat, which I would row out

into the middle of the lake when it was calm; and there, stretching out

full-length in the boat and turning my eyes skyward, I let myself float and

drift wherever the water took me, often for several hours on end, plunged in a

host of vague yet delightful reveries, which though they had no distinct or

permanent subject, were still in my eyes infinitely preferred to all that I had

found most sweet in the so-called pleasures of life. Often reminded by the

declining sun that it was time to return home, I found myself so far from the

island that I was forced to row with all my might in order to arrive before

nightfall.”

It wasn’t until I returned home and

looked up the passage once again that I realised he hadn’t actually been

writing about his native Lake Geneva, but a different lake – Lake Biel (or

Bienne) – further north, where he had lived for a time. Rousseau’s name is rightly

celebrated in Geneva now, perhaps the city’s most famous ‘citoyen’ even – but

the fact his brooding bronze effigy sits alone isolated on a little island

maybe says something about the contemporary esteem he was once held in by his fellow

Genevans during his own lifetime. His final resting place is in the suitably

august crypt of the Pantheon in Paris. He had lived out his last years in exile

in France and died there in 1778. The statue on the island in Geneva was

erected in 1834. Sitting on the train I was sure most people here would know

who Jean Jacques Rousseau was, but how many people I wondered would recall the

enigmatic Monsieur Razumov? An intense, and darkly introspective Russian

student, sat scribbling away in the shadow of that monument. Not many I

suspect, and not least because he never existed – or at least, he has only ever

existed in the mind’s eye of his creator, Joseph Conrad, and the many devotees

of Conrad’s novels, particularly those who have read and enjoyed Under Western Eyes, his tale of exiled Russian

revolutionaries in Switzerland.

I suspect I’m not the only person

who has ever made a pilgrimage to that spot for Joseph Conrad’s sake, rather

than for Jean Jacques Rousseau’s; but it did seem a trifle mad to do so in a

slim spare hour before catching a flight. I couldn’t not though. I’d passed

through Geneva three times that year already, once by road and now three times

by rail, but there hadn’t been time before to make this little detour. I’m very

glad I did though, because Under Western

Eyes is a very special book for me. I’m sure we all have them. They are

that one book – usually a novel, often read early on in our lives – which

really connects with us. There maybe many other books which speak to us just as

clearly in later years, but there’s something very special and absolutely

unrepeatable about that first novel which sucks us so completely into its world

that it changes us and informs our outlook on life forever thereafter. Under Western Eyes was that book for me.

Its characters and events seemed so real and so vivid that I could picture them;

and then, to find that this place too, was real, surprisingly only reinforced

the imagined reality. I could picture Razumov sitting there, scribbling his

informer’s notes, as if they were memories of my own, of events which I had

witnessed for myself even.

I remember when I first read that

part of the book I promised myself that one day I would visit this spot. I was

15 at the time, and almost 25 years later I’d kept my promise. Every 10 years I

re-read Under Western Eyes. It’s

interesting to see how the book transforms each time I read it, reflecting on

it at different points in my own life, the story seems to change ever so

slightly as I get older. I see things I’d missed before, or find I’ve

remembered certain details incorrectly, or even added elements in my mind.

Certain stories do that – they live within us as much as they live within the

covers of their books. I’ve now read it three times straight, and I’ve dipped

into it countless times. I’ve read many critiques of it too. But it’s not

simply this book alone; if you like one novel by Joseph Conrad you tend to like

them all – confirmed Conraddicts, in

that sense, are no different from the devotees of Dickens, or Austen acolytes,

or whichever writer you care to name.

One of the reasons why this book

may have connected with me though may in fact have been the thought of this

place itself – the Île Rousseau. This thought struck me, oddly enough, remembering

that passage of Rousseau’s as I sat on the train looking out over the waters of

the lake – thinking about Rousseau’s notions of escape, the need to be alone –

how we each need to seek our own solitude sometimes. Like Razumov sitting

scribbling here on the Île Rousseau; like Rousseau himself drifting with his

idle thoughts in his rowing boat on Lake Biel. Wherever I’ve lived I’ve

always found a spot I like to go to, simply to sit and think, or to sit and

read. It’s usually a pleasant place with a nice view, often somewhere out in

the open. Where I grew up it was a hilltop overlooking a grassy field not far

from my school; when I lived in Stoke Newington it was a particular bench by

one of the ponds in the local park; and, when I lived in Tokyo, studying

Japanese, it was a particular grassy spot in Shinjuku Gyoen, beneath the

swirling cherry blossom in Spring. Wherever I go, I realised as I sat in

another taxi racing me back to Geneva Airport, even if I’m only there for a

short time, I tend to find my own Île Rousseau.

Also on 'Waymarks'

Click on the old images for links to their on-line sources. All other images are by taken by me in 2014.