The First British Embassy to China, 1793-1794

Part

II – The Art

William Alexander was one of only

two artists who were officially appointed to record Lord Macartney’s embassy to

China. Of the two he was the junior draughtsman, yet his artistic

impressions of China have since become the most familiar depictions of the

mission. He made over two thousand sketches and paintings whilst travelling

through China; and, rather like David Roberts, his near contemporary’s

paintings of Egypt made some 50 years later, Alexander’s sketches and paintings

of China have become quintessential as representations of the Western encounter with Asia. They were primarily done to illustrate Sir George Leonard Staunton’s

official report of the mission (1797), as well as Sir John Barrow’s Travels in China (1804), but Alexander also

published two notable books of his own, The

Costume of China (1805) and Dress and

Manners of the Chinese (1814), both of which proved to be very popular. Alexander

was apparently able to support himself for a decade after returning from the

mission on the proceeds of exhibiting and publishing his China works. Between

1798 and 1804 he exhibited thirteen watercolours at the Royal Academy. In stark

contrast, the principal artist of the embassy was Thomas Hickey, who was a

portrait painter and a personal friend of Lord Macartney, although noted as a

great conversationalist Hickey’s idleness has since been remarked by historians

as rather curiously he apparently painted only one picture in the entire course

of the trip – whereas his junior colleague had managed to draw and paint around

270 sketches of the voyage before the mission had even set foot on Chinese

shores.

William Alexander was born in

Maidstone, Kent in 1767, the son of a coachmaker. He moved to London at the age

of fifteen to study art and was later admitted to the Royal Academy Schools

where his talent was duly noticed by Sir Joshua Reynolds. He was 25 years old

when the Macartney mission set out for China, and his diary of the mission

shows he was an energetic and engaged member of the party – yet he was rather

underrated and overlooked by Macartney himself. Indeed, much to Alexander’s

disappointment, Macartney left the two artists in Peking when he went to meet

with Qianlong for the first time at Chengde, and so it seems likely that he

only once, very briefly got to glimpse the august figure of the Emperor, and so

he had to rely on the descriptions furnished by other members of the party when

completing some of his more famous portraits and landscape views such as those

of the Great Wall. It is perhaps because of this reason that the accuracy of

some of his likenesses were later criticised by Sir George Staunton. This fact

not withstanding, the overwhelming majority of Alexander’s artworks are clearly

keenly observed; indeed, as were his diary descriptions too. The following is

an extract in which he describes glimpsing Qianlong on the occasion of the

Emperor’s return to the capital, Peking:

“As

soon as the Emperor and his retinue was seen in the distance, the Ambassador

and his suite moved toward the road and were placed within the line of

soldiers. Once the Royal procession was in earshot the Chinese band struck up a

martial air interrupted as ever by the most discordant percussion … His

Imperial Majesty was preceded by a body of horse. His sedan, surrounded by

Mandarins and cavalry, was of a rich yellow carried by 8 bearers … He looked

eminently towards us kneeling on one knee and bowing, and as he passed he sent

a message to the Ambassador regretting the Ambassador was not well, and as the

cold weather was approaching it would be better for him to return immediately

to Peking, rather than make any stay at the Yuan Ming Yuan … Next followed his

Chief Minister in a green sedan chair. He gave the Ambassador a very gracious

salute … The Mandarins employed and connected with the Embassy stood behind us,

dressed in their habits of ceremony, while we were kneeling when the Emperor

passed by. One of these, thinking my bow was not sufficiently respectful to his

monarch, actually put his hand behind my neck and lowered my head almost to the

ground. Perhaps my eagerness to see all that was possible of this splendid

sight might shorten the inclination of the head on this memorable occasion.”

The last few lines are fairly

striking in view of the fact that the ceremony of the kowtow was such a major point of contention for the British.

Indeed, Alexander had a similar run-in of his own with this particular matter

of court etiquette when he met a Qing official of the Imperial family on the

road whilst out on one of his trips to record scenes of Chinese country life,

he was forced to dismount but then refused to kneel and kowtow in the mud. On

the whole though, Alexander’s depictions of China and the Chinese speak for

themselves, and much as his verbal descriptions, they tend to be acutely observed,

largely accurate and even handed in their representation – and, as such, they

remain an invaluable record to modern scholars of the period. On his return to

England he went on to enjoy a successful artist’s career as a professor of

drawing, teaching at the Military College at Great Marlow, and then subsequently

becoming the first Keeper of the Prints and Drawings Department at the British Museum.

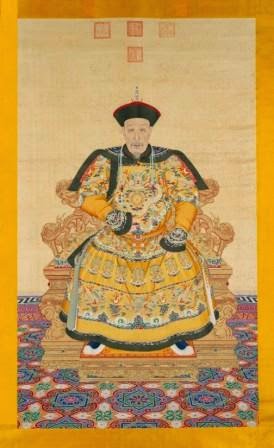

Once the embassy had returned to

Britain it did not take long for the information its members brought back to

gain a wide circulation. Indeed, just four months after their return this

painting (above) of the Emperor Qianlong was done by Mariano Bovi (an Italian artist

then working in London) and curiously, although nothing is known of how it originally

came to be produced, it is clearly a very faithful likeness of one of

Qianlong’s official court paintings (below) – which were painted on silk and

mounted on hanging scrolls, an example of which from the Palace Museum’s own

collection was included in the Britain Meets the World exhibition in 2007.

The European fascination with China

goes back a long way. From first contacts with Chinese wares brought along the

Silk Road trading routes as far back as the Roman era to the well-known travel

accounts of Marco Polo in the 13th Century; however, it wasn’t until

the Jesuit missions of the late 16th Century that sustained contact

was established. Much of Europe’s earliest knowledge of China came from the

accounts returned by these Jesuit priests, most notably Matteo Ricci. The Jesuits

gained quite a significant footing in China where their scientific knowledge,

particularly in the disciplines of mathematics, astronomy, geography and

cartography, were highly esteemed and utilised by Chinese scholars and court

officials.

Chinese commodities, such as silks,

porcelain, and spices, were highly prized items in Europe from the 14th

Century onwards. And even as early as 1604 the first Chinese books found their

way into the collections of the Bodleian Library in Oxford. Such curious wares

naturally fuelled an interest in a seemingly fabled faraway land of scholars

and artists, and the tantalising glimpses these items gave blended with fantasy

and stirred the desire to know more. From the 17th Century onwards

European craftsmen began to design ceramics, fabrics, and furniture based on

Chinese archetypes. At the start of the 18th Century the French

painter, Antoine Watteau, devised a fanciful decorative style known as chinoiserie which soon became all the

rage in Europe. A vogue for all things ‘Chinese’ from porcelains and interior

décor to pagodas and dragon motifs adorning parks and palaces ensued. A

Chinese-style bridge was even built over the River Thames at Hampton Court.

The fashion for chinoserie in Britain initially peaked

in 1750s and 1760s, but was revived by the excitement surrounding Macartney’s

embassy, and perhaps reached its apogee in the manifestation of George IV, the

Prince Regent’s sumptuously extravagant and distinctly over the top Royal Pavilion at Brighton. Built between 1787 and 1823 in the “Hindoo style”,

looking rather like the Taj Mahal outside, inside it was decorated (in 1802) with

a profusion of Chinese motifs, some of which were directly based upon William

Alexander’s artworks from the embassy, as well as an enormous chandelier

weighing over one ton which was decorated with silvered dragons. Such lavish

‘orientalizing’ provided ample fuel for stoking contemporary satires, mocking

both Macartney and the famous contretemps over the kowtow and later on mocking George IV by depicting him as an

‘oriental despot’ surrounded by opulence and ‘oriental luxury’ whilst receiving

Lord Amherst, Britain’s second failed Ambassador to China in 1816.

Back to Part I - The Embassy

References

Aubrey Singer, The Lion & The Dragon: The Story of the First British Embassy to

the Court of the Emperor Qianlong in Peking, 1792-1794 (Barrie &

Jenkins, 1992) – contains a good selection of artworks from the embassy by

William Alexander and other members of the party

Qian Chengdan & Sheila

O’Connell, Britain Meets the World,

1714-1830 – The Palace Museum (The Forbidden City Publishing House, 2007)

Edward Said, Orientalism (Routledge, 1978)