To

the Great Emperor of the German Empire.

The

war in Europe is a matter that does not concern us, the Chinese people, and as

Your Majesty knows the world is full of people with greater talents than we

have.

However,

as the ancients have said, a model emperor would be a brave warrior and

merciful: however, if one loves war for its own sake and treats human lives as blades of grass, you will invoke

the anger of the gods.

We

Chinese came to Europe as neutrals, our aim is to make a paltry living; however,

the war made our journey to Europe somewhat less than peaceful.

An

examination of the world situation now shows that within the universe we are

all one family, and a virtuous ruler would seize this opportunity to put

righteousness before profit, to follow the will of the gods and the wishes of

men, to stop the evil of the world and together with other nations create a new

world. A virtuous ruler's name will be remembered for ten thousand generations,

so why not halt your troops and select

an auspicious location to build a palace [of peace] where all the

world's powers could meet and create a peace that will last ten thousand years.*

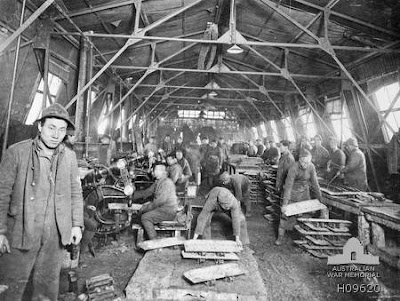

This letter to

Kaiser Wilhelm II was written by a Chinese labourer named Yuan Chun. No one

knows if it was actually ever sent to the Kaiser. The text quoted above was

transcribed into a notebook which is preserved in the archives of the Imperial War Museum in London. But as a voice from the time it tells us something of the

attitude of an ordinary Chinese man who was working behind the Allied front

lines in the closing years of the First World War. He was one of some 135,000

similar men who worked as contracted labourers, mainly in France – but also in

other parts of the global conflict zone. They didn’t fight – at least not in

the sense of seeing active combat, they weren’t soldiers – but they did help

the Allied war effort by digging trenches, filling sandbags, loading and

unloading supplies from ships and trains; as well as undertaking more skilled

labour, such as repairing tanks and artillery. After the war, completing the

full terms of their original work contracts, they stayed on into the early 1920s and

played a vital part in the recovery efforts – they repaired roads, cleared the

battlefields of unexploded ordnance, collected the bodies of the dead, dug the

neat rows of graves in the vast cemeteries; indeed, some were skilled stone

masons who carved the distinctive white headstones. And yet now, almost one

hundred years on, they are almost all but forgotten.

Very little mention

has been made of them or their undoubtedly important contribution to the Great

War in the official record or the many histories of the conflict which have

been written in the years since 1914-1918. Indeed, until very recently I could

only find one book which looked at the British Chinese Labour Corps (CLC), and

that book was privately published and so hard to find. But happily, perhaps

with the approach of the Great War’s centenary, over the last few years a

number of works have begun to appear (some of these new titles are listed at

the end of this piece). Other efforts are also in process with the aim of raising

a greater awareness of the involvement of the Chinese labourers, as well as initiatives

to ensure that recognition is suitably preserved thereby commemorating the

hardships they endured and the great sacrifices they made – many of the

labourers were laid to rest in war cemeteries across the globe (particularly in

France), looking identical to the graves of the soldiers their work supported.

|

| The Imperial War Museum, London |

Earlier this

month, on May 4th in fact, I attended a one day symposium at the

Imperial War Museum, organised by Anne Witchard of the University of

Westminster, entitled: China & The Great War. A number of academics spoke on different aspects of the Chinese

labourers (and the British Chinese Labour Corps in particular), sharing

resources and giving insights into new topics of current research, with

interesting and challenging discussions following on from most of the

presentations. Paul Bailey (University of Durham) began the day with a paper

entitled ‘From “Coolie” to “Transnational Agent”,’ looking at contemporary

discourses which have centred on the Chinese labourers within China, attempting

to place these in the context of broader global labour movement studies of the

period. The Chinese involvement with the First World War came at a pivotal

moment in China’s national history, with its transition first from a monarchy

to a republic, then through civil war to the socialist republic that it is today (with exception of the island of Taiwan, which still remains under the

political control of that first Republican Government). Hence the significance

of this key moment in China’s history subsequently remains a real problematic

for China’s national discourse even to this day.

Paul Bailey’s

talk paired neatly with a later talk given by Xu Guoqi (Hong Kong University),

and sparked a lively debate in the questions afterwards, asking “what is

China?” and “what is Chineseness?” – questions which form the focus of Xu’s

current research. As already noted, the Great War came at a crucial time when

China was in the process of redefining itself in response to pressures from

within, but also overwhelmingly due to pressures imposed from without as the

forces of Western imperialism, which had been increasingly encroaching on

China’s sovereignty since the 19th century, were now pushing China

almost to the brink of break-up and dissolution. Hence too, the significance of

the date on which this symposium was being held – May 4th, with its

historic, student-led uprising on that date in 1919. If China needed to reshape

itself in the wake of the Great War, particularly given the disappointing

outcome for China of the Treaty of Versailles, in order to properly join the

global community of nations on an equal footing, how should it define itself? –

In that sense, Chinese society at the time was asking itself – what essentially

is this unique notion of “Chineseness” and how should it inform China’s new

‘geopolitical’ identity?

Elisabeth Forster

(Oxford University, China Centre) continued this theme with her examination of

the “New Culture Movement” which arose from the events of May 4th

1919, largely shaping the “brand of modernity” which we find very much embodied

in the China of today. Examining the role of contemporary newspapers in

bringing together the students and academics of the May 4th Movement

with the popular embrace of the ideas informing the New Culture Movement raises

interesting questions concerning the connectedness of culture and politics at

the time, perhaps highlighting how Confucian notions coincidentally became

allied to the popularisation of Marxism and the rise of ‘plain language’ (baihua) in ordinary Chinese society.

Other talks given

as part of the symposium largely focussed upon the British Chinese Labour

Corps. Established by the British Government in the closing years of the

conflict, with the approval and encouragement of the then Chinese Republican

Government, the British War Office recruited a force of some 96,000 labourers

who were transported to Europe and Africa to work under contract ‘safely’

behind the lines to support the war effort, thereby freeing-up able bodied

servicemen to concentrate on the business of fighting at the Front. By no means

soldiers, paradoxically these men were drilled and lived under army rules and

strict discipline in closed camps under the charge of British military

officers. As such, and despite such a narrowly regimented work system, these

men still retained their own sense of self-worth and often collectively

organised themselves to take action when needed to assert their rights, for

instance through organised protests or strike action (a fact which has since

proved problematic to those who might wish to portray them wholly as victims of

Western imperialism).

Mauriuz Gasior

(Imperial War Museum) gave an introduction to the IWM’s photographic archives,

both official and unofficial, relating to the CLC – prompting helpful discussions

over some of the descriptive captions accompanying the documentation of some of

these images regarding the activities and details they depict.

Laura Spinney

(independent science writer & journalist) gave a fascinating insight into

the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918 (which killed more people globally than each

of the two World Wars put together), examining how this might or might not have

been connected to the movement of US soldiers and/or the Chinese labourers and

the camp-life to which they were each largely confined as perfect containment

and breeding grounds for Spanish Flu.

After which

Gregory James (University of Exeter, now retired) gave a surprisingly exuberant

analysis of the statistical realities of the number of Chinese fatalities which

occurred. Using the enormous figures frequently claimed in the media as his

launching point he then proceeded to elaborate the documentary records which

belie the realities concerning the fatalities which occurred among the Chinese

labourers during the war and in the years immediately after when they were still

under contract. He has done this by means of an exhaustive trawl through the

official War Office records, correlating them alongside other primary sources,

such as the records of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, ship’s records,

and the like, in order to produce an impressively detailed and comprehensive

computerised and searchable database. This dataset reveals that the number of

Chinese who were killed or died by other causes during the conflict aren’t

anywhere near as high as some of the inflated claims of around 10,000-20,000

(even 30,000 in one instance) with the actual estimate being closer to somewhere around 5000-6000 – although,

given the gaps, potential errors, and mismatches in the records, ultimately the

real figure will probably never be known. This database is clearly an important

historical resource, but sadly at present it is not publicly accessible; during the final

Q&As the audience expressed the hope that this resource might eventually

find a suitable home at some point in the future, so that this valuable dataset

isn’t lost.

Initially I was

drawn to the topic of this symposium as the result of a tangent to my own on-going research. I’m very interested in the British Consular Service in China as well

as the Chinese Maritime Customs Service, and many of the personnel of both institutions

‘joined up’ in order to contribute to the war effort by serving with the CLC.

Their language skills and their cultural knowledge of China was seen as a key

element in the smooth functioning of the CLC battalions, with many of them

teaching fellow British Officers basic Chinese language, as well as liaising

with and organising the labourers themselves. Several of the British consular

officials I have been researching, including Louis Magrath King, served with

the CLC in France. His father, Paul Henry King, who was based at the Maritime

Customs office in London at the time, even facilitated and organised the

sending of Chinese musical instruments to the CLC labourers in France for their

recreational amusement, hoping to help them feel less far from home. Hence,

this study day helped broaden my knowledge of the topic and gave me a number of

insights and pointers to resources which might be of future use if I am able to

expand and make something concrete out of the few things I’ve found so far in

the official archives. Who knows – watch this space, as they say!

Two films were

shown during the course of the day. The first, which was screened in the middle

of the event (just after we returned from a fantastic buffet lunch), gave some

background to the ‘Ensuring We Remember’ campaign which hopes to establish a

permanent memorial to the Chinese labourers, as well as efforts and initiatives

to promote education and better awareness.

The symposium was

rounded off with a short documentary film about a play, The Forgotten of the Forgotten, which the theatrical creative

team at ‘Moongate Productions’ hope to develop, similarly to shine a greater

light on the Chinese labourers, their crucial contribution to the Great War and

the sacrifices entailed. See a trailer for the play here.

The symposium was

an interesting and enjoyable event which was clearly very useful to all those

who attended it. Warm thanks are due to Anne Witchard. I’ve attended a number

of conference events which she has organised, particularly her ‘China in Britain’ series at the University of Westminster, and I’ve always come away

from her seminar events with masses of useful notes, piles of new contacts, plus

heaps of new ideas and inspiration for my own research. See the 'Translating China' website.

Further

Reading:

Patrick

Boehler, ‘The Forgotten Army of the First World War: How Chinese Labourers Helped Shape Europe’ (SCMP Chronicles, South China Morning Post, 2016)

Brian C.

Fawcett, ‘The Chinese Labour Corps in France, 1917-1921’ in Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Hong

Kong Branch (Vol. 40, 2000), pp. 33-111 [* inc. the letter quoted at the

start of this piece]

Gregory James, The Chinese Labour Corps, 1916-1920 (Bayview

Educational, 2013)

Daryl Klein, With the Chinks (Bodley Head, 1919)

Mark O’Neill, The Chinese Labour Corps (Penguin, 2014)

Michael

Summerskill, China on the Western Front (privately

published, 1982)

Xu Guoqi, Strangers at the Western Front: Chinese Workers in the Great War (Harvard University Press, 2014)

To mark the centenary of the Great War

Penguin have published a series of ‘Penguin Specials’ which are short books

examining various themes and topics relating to China and the War of 1914-1918.

I’ve read quite a few of these and they do make very good and highly readable

(accesible rather than heavily academic) introductions. Find out more about the

series here.

Click on any of the images above to follow a link to its source, if not my own photo.