“Why

do we react so strongly to certain places? Why do layers of story and meaning

build up around particular features in the landscape?”

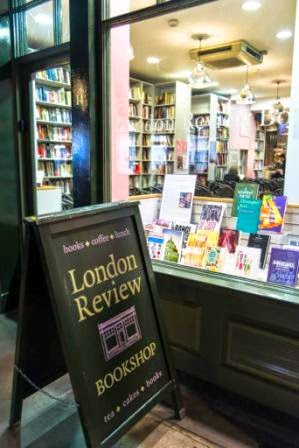

These two questions are posed on

the flyleaf of Philip Marsden’s most recent book, Rising Ground. His book also lent its title to an interesting event

which I attended at the London Review Bookshop last Tuesday. Rising Ground – Place Writing Now

brought together Philip Marsden and two other writers, Ken Worpole, and my

friend, Julian Hoffman, in a discussion chaired by the Whitechapel Gallery’s

Film Curator, Gareth Evans, to unfold the question – what is place?

“Writing

about place,” is, according to the event blurb, “a sub-genre of travel writing that subverts it by being about staying

put, rather than moving.” It was a fascinating evening which certainly helped

broaden the horizons of the mind. Each of the three writers was in agreement

that the idea of place is intrinsically linked to perception. In using the

framing device of place there is a clear distinction between knowledge and

experience. We might know a particular landscape as intimately as another

person in the detailed terms of its geography, its topography, its history, or

how it might have changed or been changed over time, but that other person may well

have had a radically divergent experience of that same place to our own.

As Julian Hoffman writes in his

book, The Small Heart of Things --- “Place

has a profound bearing upon our lives, from the countries we are born into, or

end up inhabiting, to the light, landscape, and weather peculiar to our home

regions. Each has a say in shaping our cultures and souls.” Our

relationships to the places we inhabit or simply pass through can be deepened

through ‘an equality of perception’ if we only stop ourselves and take a moment

to examine it – perceptions small and fleeting can be just as significant to us

as grand vistas and imposing, centuries old scenery. Awareness is the key, as

Hoffman goes on to recount: “One autumn,

while putting the shopping in the bed of our truck, I watched a kestrel arrow

low over the supermarket car park, snatch a small mammal from an abandoned lot

piled high with rubble and debris, and settle on a hummock of broken concrete

beneath a streetlamp to feed. It was so close that I could make out the black

fretwork on its cinnamon back, and our eyes locked together when its head

suddenly swivelled. Shoppers pushed their trolleys past me, and I could hear

the slam of closing doors, but I was so caught up in the eyes of the kestrel

that I just stood there with a bag dangling from my hand.”

Each of the three writers spoke

about particular places they have come to know and explored intimately, which

they have then gone on to write about. For each, the motivations and modes of

perception may have been different yet all three were deeply rooted in the

concept of being at home. In this context, Hoffman’s favourite idea expressed

in the words of the poet, Rainer Maria Rilke, that “everything beckons us to perceive it,” was frequently quoted and

referred back to by each of the writers in relation to their own work and

experiences with regard to place. For Marsden it is a personal search for the

spirit of place; for Hoffman it is about being at home in a beckoning world;

and, for Worpole it is about questioning received opinions, and, in so doing,

forming our own ‘re-representations’ of what a particular landscape is, or

represents, to us personally.

Philip Marsden’s most recent book, Rising Ground, very

interestingly for me (although I’ve yet to read the whole book) explores the

wider locales around his home in Cornwall. Leafing through the book I can see

many references to places both widely known and more obscure which are very well

known to me having grown up during long childhood summers spent in that

particular county. It will be interesting to see how different or coincident my

experiences of these places will measure against his own. Julian Hoffman’s wonderfully

lyrical book looks at his adopted home in Greece by the Prespa Lakes, located

in a transnational boundary park whose shores are also shared by Albania and the

former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia – with all the complicated cultural

history and diversity that such human imposed national boundaries have brought

to bear on the everyday lives of those people sharing a home and a personal

heritage in that locale. Ken Worpole’s most recent book, The New English Landscape, is a collaboration with the

photographer, Joseph Orton, which proposes a new paradigm for topographical

beauty based on the post-industrial landscape of the Thames estuary, another

part of the world closely connected to me as I now live only a few yards away

from the banks of this great river.

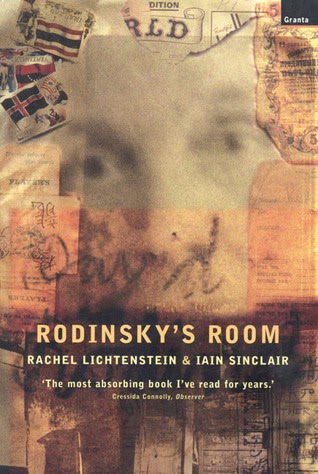

There are many ways to experience

and to describe place. Personal response is one means; another might be through

the stories of other people, of which the writings of Rachel Lichtenstein were

cited as a foremost example. Indeed, her Rodinsky’s Room (written with Iain Sinclair) is a fascinating book

– mysterious and moving by turns, in the narrative arc of her investigations

into the remnant world of one man’s vacant home, still filled after many

undisturbed years with all his abandoned possessions. A thoughtful exploration,

forlorn but ultimately uplifting in its sifting through the accumulated layers

of perception, projection, and the consequent misconceptions which seemed to

have accrued through time, until person and place are ultimately, in several

senses of the word, – relocated.

As Philip Marsden noted there can

be ‘a cacophony of interpretation’ which builds through time in relation to

particular landscapes. These can be both positive and negative. Whether it be a

depressive dismissal of a decaying post-industrial landscape, or the idealised

projections through which an unknowable Neolithic landscape might evocatively

enter and captivate our imagination, or vice versa – these surmises probably

say more about us and the nature of ourselves than the true essence of such a

landscape itself.

Writing about place can be a means

of ‘digging in and putting down roots,’ or it can be about looking back after

displacement and viewing the place from which we’ve come with eyes renewed; our

reflections become refracted, lingering resonances reverberating in unexpected

ways – we may even end up feeling closer to the place we’ve left simply because

we’ve left it. In this sense, opening yourself to a new way of perceiving

somewhere – ‘unfolding place’ – is a renewed way of experiencing it. As Ken

Worpole observed, accepting a ‘cookie cut’ notion of what a place is like merely on the say-so of other

people is simply a way of denying ourselves our own experiences, and thereby depriving

ourselves of our own intuitive responses, which – if we stopped to examine them

– may well be surprisingly different to those of the hive mind. Rural and urban

spaces need not necessarily be seen in opposition or viewed as enemies of one

another. They may even be closer (physically) and more closely interlinked (on

multiple levels) than we realise; by putting ourselves (physically and mentally)

in motion we can exchange one for the other more completely than we might

otherwise have assumed.

Just as those living transient

lifestyles in a constant state of motion – such as hunter-gatherer communities,

or nomadic shepherds, who continually relocate and renew their home-bases, and

so are seen to be idyllic, happy, and at ease in their landscapes, whereas

sedentary farmers are said to hate

the land which they feel chained to –

so we can see how perceptions of place drawn from outside and inside can differ

and perhaps are not so clearly cut after all. Just as landscapes can bleed

gradually, one into another, so too can our perceptions of place, as well as

other people, and our own individual and collective locations within these landscapes

which we have shaped into being as the places which we inhabit – the world

around us, which we call our own whilst simultaneously sharing it with others.

Rising Ground – Place Writing Now at the London Review Bookshop, well attended

with many thoughtful questions and observations from the audience, was a

thought provoking and enjoyable evening. One which certainly made me see the

world rather differently than I perhaps had done so before. I’m sure the

thoughts and ideas which this evening inspired in me, and which I’ve tried to

capture here, will linger long in mulling, and so permeate into my own

perceptions of place renewed.

See 'Person & Place' for my review of a similarly themed event on 'Capturing a Sense of Place' with the writers Mahesh Rao, Colin Thubron & Tracy Chevalier at Daunt Books earlier this year.