“There

was a morning drizzle at Victoria Station, at the end of February 1935 –

porters carolled “Mindyerbackspliz” and I murmured to someone: “Yes, send

letters to Calcutta, poste restante, but we shan’t get them till we return” – a

copy of Lost Horizon was shoved into

my hand, two years’ supply of toothpaste was left behind, and the train moved

out. Red brick suburban houses slid by, a butcher’s cart on its rounds, and the

clipped hedges of Kent. Good-bye till 1937.”

It’s a familiar tableau at the start

of any travel book – leaving the safety and the comfort of the mundane,

day-to-day world on a voyage into the unknown; far from the usual trammels and

travails of civilisation, travelling into uncharted wilds. In this case the

book is a lesser known one. Sadly so, as it’s an excellent read – well worthy

of a reprint as one of Eland Books’ rescued travelogues. The passage above

comes from the opening of Black River of

Tibet, by John Hanbury-Tracy (1938). It all began in John Hanbury-Tracy’s

club near Piccadilly over a glass of beer, sitting in company with his friend

Ronald Kaulback, who suggested they should go on a two year expedition in

search of the source of the Salween.

| Surveys and Explorations in Himalayas and Central Asia, 1934 |

“But

the Salween river? I had never heard of it [writes Hanbury-Tracy]. And why would it take over a year to reach

the source? I searched about for a map of Asia, and opened it at Burma. Yes,

there it was, a large river flowing into the sea a short way east of Rangoon;

the Salween. I followed it up, northwards. It crept along the edge of Burma.

There were dots in places, and that meant it was unexplored. I began to like

the Salween immensely.”

|

| Ronald Kaulback (left), with Shödung Karndempa, Governor of Zayul (centre), and John Hanbury-Tracy (right) |

John Hanbury-Tracy and Ronald Kaulback

were both young men at the time, in their mid-twenties. Kaulback was already

familiar with this region of southeast Tibet having accompanied the plant

collector, Frank Kingdon Ward on his 1933 expedition. Reading the travelogues

of these men today there is a real echo of the exotic and the sense of mystery

which pervades James Hilton’s eponymous adventure novel, Lost Horizon – but far from the sense of “Boys Own” nostalgia such

tales might evoke today this was a kind of zeitgeist which Hanbury-Tracy,

Kaulback, Kingdon Ward and others were actually living at this time. They very

much saw themselves as intrepid explorers filling in the last blanks on the

map.

|

| Gorge of the Ling Chu, near the confluence with the Salween |

“Near

the north-eastern corner of Burma the mountains seemed to be trying to strangle

three great rivers, the Yangtze, the Mekong and the Salween. Beyond that the

rivers spread out in a fan, with the Salween as left-hand or Western rib.

Together they drained an enormous area. Up there, in eastern Tibet nearly

everything was marked in dots, both roads and rivers. Several place-names had

an interesting note of interrogation after them. Even the mountain ranges were

drawn in tentatively, and heights were hardly shown at all. A few routes were

definite, routes followed by European travellers. But there was a lot of blank

space in between. And, except at two or three points where it had been crossed,

the upper course of the Salween where it was called the Nak Chu (Black River),

some hundreds of miles in length, was entirely conjectural.”

It is a colonial fallacy, of

course. These regions weren’t entirely unknown. There were roads and towns as

Hanbury-Tracy references, and before they set out they had to secure the

necessary travel permits from the British-Indian and Tibetan Governments in

order to allow them to enter the region and to make use of the local porterage

system. In most parts they were following routes which had been trodden for

centuries by traders, pilgrims, and soldiers travelling from settlement to

settlement, valley to valley. And each region was clearly demarcated and already mapped out in

the collective local mind. Indigenous administrative zones delineated economic

and territorial distinctions which might not be readily apparent to incoming

outsiders, but these boundaries represented a fixed reality which such European

travellers often ran up against when local officials quibbled over the validity

of their passports and as a consequence sometimes made them wait, wasting

months in limbo on some occasions.

|

| A Chorten and Mani Stone pile, part way between Situkha and Wosithang |

If permission to proceed was

eventually granted sometimes the seasonal changes in weather conditions meant

they were unable to continue hence they’d still have to turn back anyway. Whether

or not this kind of delay was a deliberate ploy on the part of the local

officials could be a moot point – there could be any number of reasons

prompting such hold-ups. For instance, sometimes a regional governor might be

worried that some parts of his territory were too dangerous (due to roaming

'brigands' perhaps), and so they were understandably reluctant to let foreigners

proceed if they could not guarantee safe passage. Explanations, rather than revealing

genuine reasons, could well be fudged in order to save face.

|

| Watching the 'Devil Dance' at Nakchö Biru |

Kaulback and Hanbury-Tracy

experienced a delay of this kind, waiting over two months at Nakshö Biru for

confirmation of their travel permits during which time they were treated very

hospitably even though they effectively felt like prisoners there. The fact

that Hanbury-Tracy had grown a magnificent beard during the course of the

expedition, of which he was duly proud, didn’t help their situation – as they

later came to the realisation that it had fuelled suspicions that he might be a

Russian spy! … Ultimately when their papers were duly verified and they

attempted to continue on towards their goal of reaching the source of the

Salween a combination of adverse weather, due to the advanced season, and the

unsafe conditions, due to fighting on the route ahead meant Kaulback and

Hanbury-Tracy reluctantly decided to turn back. It was a sad defeat. A defeat due

entirely to circumstances beyond their control, having been deeply frustrated

by the long wait for confirmation of their credentials, something which they

thought was wholly unnecessary in the first place.

|

| Crossing the Salween-Brahmaputra watershed, ascending a mountain scree slope |

|

| Crossing a rope bridge attached to a bamboo slider over a fast flowing river |

|

| Crossing the Ata Kang La and heading down the glacier, trekking through snow |

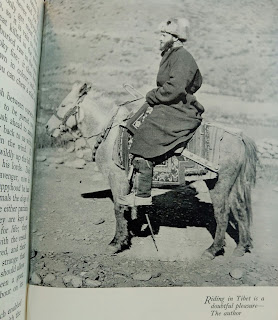

But the sense of adventure their

journey evoked was certainly real enough. Some of the terrain Hanbury-Tracy and

Kaulback travelled through could physically test them and their pack animals to

the limit; crossing high mountain passes and precipitously steep scree slopes,

as well as fording fast flowing rivers or dangling from precarious rope

bridges, battling their way through ‘white-out’ snow blizzards or intense tropical

heat, the chances of physical injury, illness, or worse were regular risks

encountered on the road. Plus, in the lowland jungle regions there were leeches

– lots of leeches – which got into

their clothes and left their skin peppered with bleeding sores. They used to

play a dark-humoured game, keeping competitive tallies as to who had accrued

the most bloodsuckers each day! – But such journeys were entirely justified in

their own eyes. They were made in the service of science. Hanbury-Tracy hints

that the thrill of travel was in fact the real lure, but taking two years out

was no jolly ‘gap year’ jaunt simply in and of itself.

“With

the goddess of Science as a sure shield against a barrage of questions we

pushed forward our little plans. But the goddess made her own demands.

Entomologists wanted us to look out for a particular species of tipulida, and

that I discovered meant a daddy-long-legs. Botanists asked us to collect every

possible kind of leguminous plant, meaning, to a non-botanist, those that

looked like sweet peas or vetch. While ornithologists wished to know how high

above sea-level a certain type of diver, minutely described, built its nest.

And Ron was to collect rare snakes, in a jar of “pickle.” Already there was a

glimmer of respectability about our schemes.”

There is a great deal of humour in

Kaulback and Hanbury-Tracy’s travel narratives which belies the serious science

they pursued whilst on the road. Kaulback published his own account of the

expedition, simply titled Salween (1938),

later the same year as Hanbury-Tracy’s Black

River was published. Reading their travelogues in tandem is a rich and

rewarding experience. I felt like I got to know both of them intimately, and moreso

that I might well have liked and got on well with both of them. There’s

something about Hanbury-Tracy’s writing which puts me in mind of myself (though

I only wish I could write half as deftly as he does!), and Kaulback rather

reminds me of my grandfather, not least because my grandfather once got himself

into a similar, perilous scrape on a cliffside in a disused quarry near his

house (whilst out blackberrying, I think) as Kaulback recounts during his Tibetan

travels with Kingdon Ward in 1933: "The

next few minutes were an entire blank, until I found myself, still terrified

out of my senses, sitting on a wide ledge, clasping a bush as if I loved it,

and wondering why I had ever left England."

Kaulback had first met Kingdon Ward

at the Royal Geographical Society whilst he was learning various techniques required

for surveying in the field. When asked to provide a character reference

Kaulback’s old tutor at Pembroke College, Cambridge, memorably wrote back

saying: “I have known Kaulback well

through three tumultuous years at this College, and can confidently recommend

him to you as an explorer-companion, or as a buccaneer, or probably best of all

as the president of a South American republic.” … Undeterred (or perhaps

inspired) by this quixotic recommendation Kingdon Ward took him on. As Kingdon

Ward later wrote in his introduction to Kaulback’s first book, Tibetan Trek (1934): “I was impressed by his sound common sense and his anxiety to take

work off my shoulders. Nor did he shirk responsibility. For the first few days

after we left civilization, I was worried about him. Had I made a mistake? But

I need not have alarmed myself. From Rima onwards, when he had work of his own

to do, he began to shape into the real thing. His work was astonishingly

accurate and neat. Above all he was thorough. He took an interest in

everything, and was an excellent companion. I never wish a better.”

|

| Frank Kingdon Ward |

Although Kaulback was only

twenty-four years old at the time he quickly won his explorer’s spurs on this

expedition when he unexpectedly had to cut short his participation and lead the

return party back to India without Kingdon Ward at an inclement time of year.

As Kingdon Ward described it: “To return

through the Mishimi Hills during the rainy season was probably impossible [this

was the route by which they had already travelled]; there remained only the long and difficult route via Fort Hertz and

Burma. Could Kaulback do it? I believed he could, although the crossing of the

Diphuk La had only twice been performed by white men, on both occasions by

experienced travellers.”

|

| Kaulback's last sight of Kingdon Ward, 1933 |

One can see a real progression in

Kaulback’s two books as he rapidly shapes up into a serious

scientifically-minded explorer. He developed a keen interest in snakes and

often discomforted his companions by keeping the live specimens he collected

inside his shirt. On one occasion he was bitten by a very poisonous snake but

managed to isolate and cut the poison out before it could take effect. Hanbury-Tracy

went on to become an accomplished traveller, noted for his journeys in South

America collecting plants for the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew. On their return

from Tibet they presented the findings of their expedition to the Royal Geographical

Society and were duly praised for their efforts mapping vast regions of the

territory they covered (25,000 square miles) and collecting numerous specimens

of flora and fauna which they sent back to the British Museum of Natural

History, even though they were unable to reach the source of the Salween for

reasons beyond their control. The two men may well have undertaken a return

expedition had the Second World War not intervened. Instead they each found

themselves dedicating the war years to fighting the Japanese in Burma, as part

of Force 136 (the SOE, Special Operations Executive), which conducted highly

dangerous reconnaissance missions and sabotage raids, often behind enemy lines.

Kaulback was later awarded an OBE (Order of the British Empire) for his wartime

service.

Kaulback and Hanbury-Tracy’s Tibetan

travelogues represent a confluence of romanticism and rationality. The romance

of venturing into the unknown, travelling “off

the edge of the map” (a favourite phrase of Kingdon Ward) “leaving civilisation behind” (a

favourite of Kaulback’s). And the rational minded pursuit of science –

surveying, charting, collecting, classifying – making the unknown known. Plus,

perhaps equally as important, a process of shaping the self through hardship

and feats of endurance. In many ways, in contemporary parlance, this was the notional

‘white man’s burden’ made manifest. Knowing oneself and knowing the world were

in essence intimately bound up in notions of ‘duty’ and the ‘noble pursuit’ of scientific exploration,

particularly when reflected through the reasoning characteristic of a typical colonialist’s

world-view.

Or as Hanbury-Tracy philosophises it: “At bottom of course nearly all exploration springs from a desire to wander, a desire which is as potent in human nature as love or hunger, but he who wanders without valid excuse is labelled Beachcomber. So public opinion has ever forced those smitten with the curse of Ishmael to present new excuses, excuses which, curiously enough, have been repeatedly responsible for new empires, new trade routes, additions to science, and fresh luxuries for the critics. And as for the sons of Ishmael, they have often found that the excuse has ceased to be an excuse at all and become a real purpose with attendant responsibilities.”

Hence, taking such travelogues purely at face value, it is all too easy to overlook the

fact that underlying these endeavours was an existing network of indigenous

people; official government permission, the grace and favour of local

governors, local systems of porterage, rules and regulations, all of which

either facilitated or frustrated the efforts of these outsiders. In studying

the travelogues of explorers such as Kaulback and Hanbury-Tracy, as well as

Frank Kingdon Ward, George Forrest, Reginald Farrer, George Sherriff and Frank

Ludlow, I find it interesting to see the same indigenous names recurring (flickering

through different, idiosyncratic renderings into English spellings) – I often

find myself wondering what these local ‘fixers’ would say if I were able to ask

them directly what they had thought of this curious group of European

adventurers, the intrepid (and sometimes eccentric) men who repeatedly engaged

them as their employers year after year. For such local agents were often more

than simply the fleet-footed facilitators of these expeditions. They often

shared their keen-eyed knowledge of the plants, birds, animals, and insects they

collected, as well as learning the careful techniques of collecting and

preserving specimens which were essential to the success of such scientific

endeavours. Such expeditions must have been characterised by a two-way flow of

knowledge borne by a mutual respect and understanding, if not always an equal

sense of appreciation or level of comprehension. These were, after all, the men

whom Hanbury-Tracy subtly yet significantly says were “our servants and also our friends.”

Bibliography

Ronald Kaulback, Tibetan Trek (Hodder & Stoughton,

1934)

Ronald Kaulback, Salween (Hodder & Stoughton, 1938)

Ronald Kaulback, ‘The Assam Border

of Tibet’, in The Geographical Journal,

Vol. 83, No. 3 (March, 1934), pp. 177-189

Ronald Kaulback, ‘A Journey in the

Salween and Tsangpo Basins, South-Eastern Tibet’, in The Geographical Journal, Vol. 91, No. 2 (February, 1938), pp.

97-121

John Hanbury-Tracy, Black River of Tibet (Frederick Muller,

1938)

John Hanbury-Tracy's Photographs of Tibet - Jacques Marchais Museum of Tibetan Art

|

| The Gya Lam, Great China Road |

|

| Crossing the Salween, via a magnificent log bridge in a sad state of disrepair |

|

| Pangar Gompa |