“Lake Leman lies by Chillon’s walls:

A

thousand feet in depth below

Its

massy waters meet and flow;

Thus

much the fathom-line was sent

From

Chillon’s snow-white battlement”

- Lord Byron

In February this year, whilst I was

on a work trip to Switzerland, I visited the Château de Chillon near Montreaux, on the easternmost shore of Lake

Geneva. The castle is one of the most famous and picturesque sites in

Switzerland, the idyllic subject of many a wistful tourist picture-postcard,

yet its long history makes for a fascinating study of kaleidoscopic historical and

literary perceptions. Its current idyllic symbolism and almost Disney-like beauty

belies a very bloody history, such that writers from earlier eras once described

the imposing ‘Bastille’-like edifice as dark, oppressive, and ugly.

The castle is thought to be over a thousand

years old, with traces of human occupation on the rocky islet upon which the

castle is built dating back to the Bronze Age – as demonstrated by excavations

carried out from the late 19th century by the archaeologist, Albert Naef (1862-1936). The oldest written mention of the castle dates from 1150. The

castle’s history is now divided into three important periods: the Savoy era (12th

century to 1536); the Bernese era (1536-1798); and, the Vaudois era

(1798-present). For much of its existence the castle was maintained as a

fortress, arsenal, and prison. It was decommissioned in the 19th

century, since when it has been preserved as a historic monument.

Set beneath a steep cliff, isolated

on a rocky island which it occupies entirely and reached by a single wooden

bridge, the castle with its tall imposing walls is a formidable mix of round

and square towers topped by red tiled roofs. With the aid of an excellent

leaflet given to you when you pay at the entrance gate it’s possible to explore

the entire castle by yourself and get an understanding of the original

functions of each of the rooms and galleries within. The building is fabulously

atmospheric, from the dank chilly airs of the lake-level store rooms and

dungeon up to the fresh airy heights of the central tower (which one ascends

via a series of creaking wooden staircases that rather reminded me of those in the

central tower of Himeji castle in Japan).

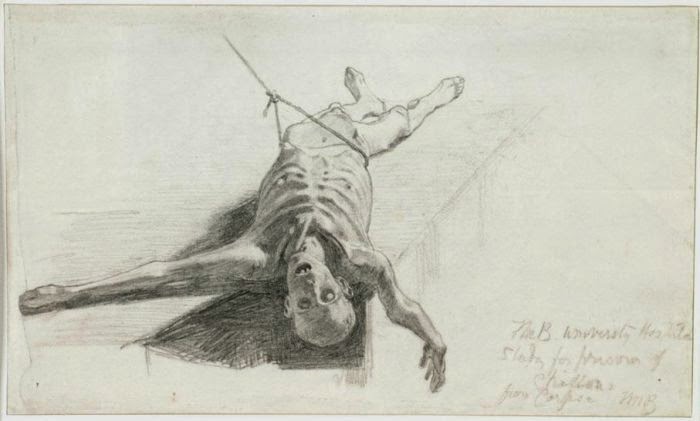

Unsurprisingly, the castle has been

the subject of much artistic and literary interest over the centuries. Notable

from the sketches, prints, and paintings of artists such as J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851)

and Ford Madox Brown (1821-1893), as well as the writings of the English

Regicide, Edmund Ludlow (c.1617-1692),

and the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) onwards. The castle is perhaps

best known by the poem The Prisoner of

Chillon written by Lord Byron (1788-1824) after he visited the castle in

1816.

“There

are seven pillars of Gothic mould,

In

Chillon’s dungeons deep and old,

There

are seven columns, massy and grey,

Dim

with a dull imprisoned ray,

A

sunbeam which hath lost its way,

And

through the crevice and the cleft

Of

the thick wall is fallen and left;

Creeping

o’er the floor so damp

Like

a marsh’s meteor lamp:

And

in each pillar there is a ring,

And

in each ring there is a chain;

That

iron is a cankering thing,

For

in these limbs its teeth remain,

With

marks that will not wear away

Till

I have done with this new day”

The

Prisoner of Chillon is actually a pair of poems (a sonnet and a longer narrative poem or ‘fable’) in which Byron recounts, and rather embellishes, the

story of the castle’s most famous captive – François Bonivard (1493-1570). Bonivard was the Prior of Saint-Victor

in Geneva and a republican opposed to Charles III of Savoy’s attempts to take Geneva.

He was captured in 1530 and held captive at Chillon until 1536. For the first

two years of his captivity he was held in comfort in the upper rooms of the

castle, but spent the remaining four in chains in the castle’s dungeon, where

he is renowned to have worn down the stone floor in pacing about one of the

pillars to which he was shackled. He was eventually liberated when the castle

was successfully besieged by the Bernese and Genovese, and returning to the

newly Protestant Geneva he was made a member of the governing Council of Two

Hundred.

The pillars of Bonnivard’s dungeon

are all inscribed with numerous names both famous and obscure from different

dates. One of these is that of Byron himself, now neatly framed, although some

doubt has been cast as to whether the poet himself actually cut it into the stone

or whether it was done by a later hand once his poem had been published and

become a phenomenal success. Either way it was of interest to me as I recall

seeing Bryon’s name scored into the old school room at Harrow (my home town)

when I visited on a school trip when I was about 11 or 12 years old – and, if

my memory serves me well, the two graffitios do look rather alike (?).

Later writers who visited the

castle took a less romantic view and have left accounts which seem to seek to

debunk or demythologise Chillon. Writing in 1833 John Ruskin (1819-1900) in particular

sought to pick some very pedantic holes in Byron’s poetic tropes: “ ‘So far the fathom line was sent’ – Why

fathom line? All lines for sounding are not fathom lines. If the lake was ever

sounded from Chillon, it was probably sounded in metres, not fathoms.” (Zzzzz

… I, for one, have never been able to get very far into anything written by

John Ruskin!). Other writers were still even less impressed with the place

itself. Writing in his diary whilst staying at the Hotel de Byron in Villeneuve

on June 12th 1859, Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804-1864) observed: “The castle is terribly in need of a pedestal;

if its site were elevated to a height equal to its own, it would make a far

better appearance.” Given its waterside setting he then compares the castle

to “an old whitewashed factory or mill.” Perhaps

Neuschwanstein Castle in Germany would have been more to his liking?

Hawthorne’s fellow countryman, Mark Twain (1835-1910), typically took a somewhat more wry or nuanced view: “I had always had a deep and reverent compassion for the sufferings of

the ‘prisoner of Chillon,’ whose story Byron has told in such moving verse, so

I took the steamer and made pilgrimage to the dungeons of the Castle of

Chillon, to see the place where poor Bonivard endured his dreary captivity 300

years ago. I am glad I did that, for it took away some of the pain I was

feeling on the prisoner’s account. His dungeon was a nice, cool, roomy place,

and I cannot see why he should have been so dissatisfied with it … He surely

could not have had a very cheerless time of it in that pretty dungeon. It has

romantic window-slits that let in generous bars of light, and it has tall,

noble columns, carved apparently from the living rock; and what is more, they

are written all over with thousands of names, some of them, – like Bryon’s and

Victor Hugo’s, – of the first celebrity. Why didn’t he amuse himself reading

these names? Then there are the couriers and tourists – swarms of them every

day – what was there to hinder him from having a good time with them? I think

Bonivard’s sufferings have been overrated.” (Mark Twain, A Tramp Abroad, 1880).

I suppose everyone takes their own

view of a place particular to themselves and perhaps their time. For me Chillon

is a beautiful and fascinating place, sublimely atmospheric, rich in literary

and historic ambience. And, for anyone of inclinations similar to mine, I recommend

Patrick Vincent’s excellent pocket-sized Chillon: A Literary Guide as the perfect exploring companion.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments do not appear immediately as they are read & reviewed to prevent spam.