I can’t believe it has been ten years

since I made this particular journey. The memories are so fresh it feels like

it was just yesterday. I’m always reminded of this journey at this time of

year, whenever I hear the sound of a sudden summer cloudburst pattering on the

green leaves of tall tress. Without a breath of wind, the gentle yet intense

sound of the rain the only thing breaking the stillness of the warm, heavy air.

It’s like an echo in time.

On 8th June 2005 we set

out from Tokyo on the ‘Odoriko’ train bound for Izu. The Izu Peninsula is only

a short distance west along the coast, originally formed from the ancient lava

flows of nearby Mount Fuji. Izu is an idyllic spot, relatively sparsely

populated given its close proximity to the vast megalopolis of Tokyo, it has a

jagged coastline looking out over a beautiful turquoise sea, and the hills

inland are covered with lush forests of maple and beech tress. It is a famous place

for its hot springs, or onsen 温泉,

of which there are said to be around some 2,300 or so.

Our first stop was the coastal town

of Atami. A short bus ride up the steep hillside took us to the MOA Museum of Fine Art. To reach this very modern museum building you have to ride a sequence

of escalators which ascend within the hillside itself. The fact that we were

the only people travelling up enhanced the serene yet surreal sense that we

were ascending into some sort of parallel dimension, yet at the top we emerged

once again to a spectacular view looking down the steeply raked hillside to the

sea.

The museum has a wonderful collection of ancient art, including a reconstruction of a famous golden tea room, based on an original tea room from 1586, in which Lord Toyotomi Hideyoshi entertained the Emperor Ogimachi. The museum itself is set amongst very beautiful grounds, with its own noh theatre stage, and it also has a small pond outside with water lilies growing within which originally came from the garden of French Impressionist painter, Claude Monet in France.

The museum has a wonderful collection of ancient art, including a reconstruction of a famous golden tea room, based on an original tea room from 1586, in which Lord Toyotomi Hideyoshi entertained the Emperor Ogimachi. The museum itself is set amongst very beautiful grounds, with its own noh theatre stage, and it also has a small pond outside with water lilies growing within which originally came from the garden of French Impressionist painter, Claude Monet in France.

Here at Atami we stayed in a

traditional ryokan 旅館,

or family-run inn. This one was particularly special as in addition to the main

ryokan building, with its large

indoor ofuro お風呂 and

outdoor rotemburo 露天風呂,

or communal baths. It also had a few small, traditional-style wooden cottages

tucked away amidst a garden which was carefully laid-out and quite ingeniously

styled to make each cottage feel wonderfully secluded, even though the grounds

couldn’t have been altogether very extensive in such a tight urban space.

Rather than taking a room in the main lodge we took one of these little

cottages.

Inside it was quite spacious, with tatami 畳, or woven-grass mat floors; shōji 障子, light sliding paper-screen doors, and its own small bathroom with piped onsen water. This ryokan was my first experience of a hot spring spa, and it was a revelation – it might sound daft, but I’ve never experienced water so thoroughly hot before! … It’s hard to describe adequately in words, but there is something almost supernatural about water which has been heated by subterranean thermal vents and then filtered through volcanic rocks before reaching the surface, still scalding hot, its steam scented with minerals and salts drawn from deep within the earth. I’m quite sure there is nothing which can ease and relax all the tensions from your muscles quite like the waters of a good hot spring! – That, combined with the perfectly honed hospitality of a traditional ryokan, is a real escape from the everyday ... A long soak in the hot waters, leaving you feeling relaxed and cleaner than ever before, followed by a beautiful and exquisitely presented feast, all freshly prepared with a careful combination of dishes, immaculately served, and washed down with a few cups of chilled sake will set you up perfectly for the night as you simply melt into the crisp covers of your futon 布団, breathing in the sweet aroma of the tatami floor all around you. I was out like a light!

Inside it was quite spacious, with tatami 畳, or woven-grass mat floors; shōji 障子, light sliding paper-screen doors, and its own small bathroom with piped onsen water. This ryokan was my first experience of a hot spring spa, and it was a revelation – it might sound daft, but I’ve never experienced water so thoroughly hot before! … It’s hard to describe adequately in words, but there is something almost supernatural about water which has been heated by subterranean thermal vents and then filtered through volcanic rocks before reaching the surface, still scalding hot, its steam scented with minerals and salts drawn from deep within the earth. I’m quite sure there is nothing which can ease and relax all the tensions from your muscles quite like the waters of a good hot spring! – That, combined with the perfectly honed hospitality of a traditional ryokan, is a real escape from the everyday ... A long soak in the hot waters, leaving you feeling relaxed and cleaner than ever before, followed by a beautiful and exquisitely presented feast, all freshly prepared with a careful combination of dishes, immaculately served, and washed down with a few cups of chilled sake will set you up perfectly for the night as you simply melt into the crisp covers of your futon 布団, breathing in the sweet aroma of the tatami floor all around you. I was out like a light!

The next day we took another train

up to Mishima, where we had lunch in an old restaurant which had been run

continuously by the same family since the Edo Period (1600-1868), then

continued on to Shuzenji. From here we proceeded by bus up into the densely

wooded hills to Amagi. Here we stayed at another ryokan which had a special association with the writer, Yasunari Kawabata (1899-1972). Kawabata is best remembered now as the first Japanese to

win the Nobel Prize for Literature, in 1968. In my bag was a copy of one of his

books – a collection of short stories which began with the tale of Izu no Odoriko 伊豆の踊子, ‘The Dancing Girl of Izu.’

The story

begins at the very ryokan in which we

were staying. The narrator, a young 20 year old student on a solitary walking

holiday, meets a troupe of travelling entertainers from Oshima Island on the

road. They become travelling companions, continuing on together from here to

the coastal port town of Shimoda. One evening, whilst sitting on the stairs of

the ryokan, he watches the youngest

girl of the troop – ‘The Izu dancer’ – performing, and falls quietly in love

with her. But as with so many of Kawabata’s stories the love is an understated

and unspoken one, a silent romantic awakening which brings a kind of inner

transcendence through both the joy and the pain of unfulfilled longing. It is a

touching and much loved ‘coming-of-age’ story. Kawabata used to be a regular

guest at this ryokan which is

decorated with old sepia-toned photographs of him. His favourite room, which he

always used to stay in, has been preserved and is now filled with his books and

mementos of his most famous short story which, so the proprietors say, was

inspired by actual events that took place here at this very inn.

“After

we passed, I looked back at them again and again. I had finally experienced the

romance of travel. Then, my second night at Yugashima, the entertainers had

come to the inn to perform. Sitting halfway down the ladderlike stairs, I had

gazed intently at the girl as she danced on the wooden floor of the entryway.”

– Yasunari Kawabata, The Dancing Girl of Izu (1925).

Our room was high up in the

building with windows looking down onto the narrow valley through which a small

stream gently bubbled and rushed over grey rocks. The special feature of this ryokan is its outdoor rotemburo which, tucked discreetly out

of sight of the main building, is set into the stream itself. There is a small

wooden roofed shelter part-way down the garden at which the bather or bathers

can disrobe from their yukata, a

light summer kimono (each ryokan

issues these to their guests and they are usually decorated with motifs

associated with that particular guesthouse), which they leave there in

specially provided baskets, along with their wooden geta 下駄 (a kind of sandal on little

stilts) as all bathers at onsen go naked,

and the communal ofuro are usually

segregated – hence anyone else subsequently approaching down the path will

notice the geta left there, but not

knowing which sex the bathers might be (and also because it is only a

relatively small bath), they will return to the guesthouse to wait until the rotemburo is vacant. Nobody stays too

long in such a hot spring bath, mainly because they are often very hot! – But

once out, one soon wants to get back in

again …

Our room was high up in the

building with windows looking down onto the narrow valley through which a small

stream gently bubbled and rushed over grey rocks. The special feature of this ryokan is its outdoor rotemburo which, tucked discreetly out

of sight of the main building, is set into the stream itself. There is a small

wooden roofed shelter part-way down the garden at which the bather or bathers

can disrobe from their yukata, a

light summer kimono (each ryokan

issues these to their guests and they are usually decorated with motifs

associated with that particular guesthouse), which they leave there in

specially provided baskets, along with their wooden geta 下駄 (a kind of sandal on little

stilts) as all bathers at onsen go naked,

and the communal ofuro are usually

segregated – hence anyone else subsequently approaching down the path will

notice the geta left there, but not

knowing which sex the bathers might be (and also because it is only a

relatively small bath), they will return to the guesthouse to wait until the rotemburo is vacant. Nobody stays too

long in such a hot spring bath, mainly because they are often very hot! – But

once out, one soon wants to get back in

again …

Naked communal bathing in Japan can

be a bit daunting for a foreigner on his first occasion (speaking for myself

here). The fear and trepidation of doing something wrong is ever present,

especially being mindful of the heavy cultural importance placed upon all the elaborate

ritual ablutions which one must thoroughly and ostentatiously be seen to

perform before one even thinks of setting a foot in the communal bath.

Cleanliness is indeed sacred in this regard ...

The first time I bravely ventured into one on my own (not here, but in Matsushima) I thought I was meant to leave even my glasses in the basket, but having walked a few paces towards the glass wall between the changing room and the baths I found I was so blind without them I couldn’t even discern which panel was the door; so deciding, even if I looked a fool, I would wear my specs into the bath, I went back and retrieved them – but my Laurel and Hardy routine only continued when I stepped through the door and my specs instantly steamed up! … Consequently I felt some sympathy when I read with amusement the following travelogue by Rudyard Kipling on his own experiences of visiting an onsen whilst journeying through Japan in 1889:

The first time I bravely ventured into one on my own (not here, but in Matsushima) I thought I was meant to leave even my glasses in the basket, but having walked a few paces towards the glass wall between the changing room and the baths I found I was so blind without them I couldn’t even discern which panel was the door; so deciding, even if I looked a fool, I would wear my specs into the bath, I went back and retrieved them – but my Laurel and Hardy routine only continued when I stepped through the door and my specs instantly steamed up! … Consequently I felt some sympathy when I read with amusement the following travelogue by Rudyard Kipling on his own experiences of visiting an onsen whilst journeying through Japan in 1889:

“Apropos

of water, be pleased to listen to a Shocking Story. It is written in all the

books that the Japanese though cleanly are somewhat casual in their customs.

They bathe often with nothing on and together. This notion my experience of the

country, gathered in the seclusion of the Oriental at Kobe, made me scoff at. I

demanded a tub at Juter’s. The infinitesimal man led me down verandahs and

upstairs to a beautiful bath-house full of hot and cold water and fitted with

cabinet-work, somewhere in a lonely out-gallery. There was naturally no bolt on

the door any more than there would be a bolt to a dining-room. Had I been

sheltered by the walls of a big Europe bath, I should not have cared, but I was

preparing to wash when a pretty maiden opened the door, and indicated that she

also would tub in the deep, sunken Japanese bath at my side. When one is

dressed in only in one’s virtue and a pair of spectacles it is difficult to

shut the door in the face of a girl. She gathered that I was not happy, and

withdrew giggling, while I thanked heaven, blushing profusely the while, that I

had been brought up in a society which unfits a man to bathe à

deux.”

– Rudyard Kipling, From Sea To Sea (1900).

After a hot soak and a lavish feast

in our room, which again was made up in the traditional Japanese style with tatami mat floors, sliding shōji screens and low tables, once

the sun had set, we ventured out for a stroll. We had picked the right time to

stay because that evening was the night of the annual firefly festival, the

first night of the year when the fireflies magically emerge and take wing. A

short distance down the hill from our ryokan

there is a little island in the river which is joined by two bridges, one to

each bank and renowned after a local legend of two forbidden lovers coming

across the bridges to meet on the island in the middle. We were given a small

paper lantern on a stick with a small candle inside by the little old lady who

ran the ryokan with her family and

set off into the night. Walking on geta

is an acquired skill. It doesn’t take long to get the knack though, especially

if you picture yourself as moving your feet and legs in the very deliberate

manner a child’s clockwork toy-robot!

Crossing the bridge to the island

was a beautifully ethereal experience for me. It was as though I had stepped

through a time-warp back to the Edo Period, as everyone there (including me)

was dressed in their yukata, the

patterns of which made it easy to discern how many different ryokan there were nearby. Through the

stark black silhouettes of the tall trees we could see the stars twinkling high

above, but down here in the pitch black shadows of the looming trees we could

see the faint wavering trails of the fireflies, green glowing dots of light, like small

constellations of wandering stars emerging both near and far. Gradually

multiplying in number as the fireflies began to come out, their strange green

lights flickering and fading in-and-out of varying degrees of brightness. As

our eyes adjusted to the darkness we could see more and more of them. People

were putting out their hands, gently encouraging the fireflies to take a

momentary rest on their outstretched fingers. I was amazed at how big, black

and ugly they were when someone lit a torch to take a closer look. Over on the

far side of the other bridge a small local TV News crew periodically lit up a

large arc lamp for a few moments to film the people milling about the island in

their yukata, it was then that I

realised I was the only westerner and indeed the only non-Japanese there.

After a while of watching the hypnotic

dance of the fireflies over the rushing waters of the river amidst the gentle,

murmuring rustle of the leaves overhead we began the climb back up the hill to

our ryokan, where we went for a late

night dip in the rotemburo. It was

even more magical lying in the hot water with the surging flow of the ink-dark stream

swirling passed on a level with the rock-lined bath, lying back and looking up

to the bright stars through the dappled blackness of the maple leaves overhead,

with an occasional stray firefly glinting through the arboreal darkness.

When we awoke the next morning I

remember thinking I’d never felt so relaxed in all my life. The combination of

bathing in the hot onsen with the

scent of the tatami floor and the hinoki 檜 (Japanese cypress) and sugi 杉 (Japanese cedar) wood timbers of

our room’s interior décor was wonderfully calming. I lay there reading Kawabata’s

words, listening to the rush of water in the river below and the gentle patter

of rain on the leaves of the tall trees outside coming in through the open

window. I could well understand why he was so at peace staying here. His

stories are all very much about images and feelings, such that his plotlines

often feel rather open and inconclusive. In that sense, especially given the

brevity of his signature so-called ‘palm of the hand’ stories, his writings are

somewhat akin to the old Edo haijin 俳人,

or haiku masters, such as Matsuo Basho and Yosa Buson. Eidetic windows into a

world of subtly waking thought. A lightness and profundity pinned in perfect

balance. It is this quality which I admire most, and it’s what draws me to

Japanese literature. I feel a deep and genuine affinity for it. I hope one day

my Japanese will be good enough to read Kawabata, and appreciate him properly,

in the original Japanese, as I currently do in translation.

From here we bid farewell to the

old lady innkeeper and her family, then set out on foot, following the path travelled in the story of Izu no Odoriko. Retracing

the footsteps of the characters through the Amagi foot tunnel and on along the

winding trails through the forest, encountering wonderful views of tumbling

waterfalls along the way. I was very much hoping to see wild monkeys, but no

such luck. The most exotic things we saw were colourful bugs and caterpillars,

plus a bright orange snake crossing the trail. The snake looked mightily

indignant at meeting us unannounced and so suddenly. After coiling itself up

into a tightly miffed zigzag it proceeded to fling itself with comic abandon from

the steep drop at the side of the trail into the undergrowth far below.

Eventually emerging from the forest,

and now with a real appetite for lunch, we found ourselves happily at a small

rustic roadside eating house which specialised in local deer meat. Here we ordered

deer sashimi, and steaming hot bowls of delicious udon noodles, all washed down

with a couple of much needed bin biru 瓶ビール

(bottles of beer). From here we caught a couple of buses to

Shimoda.

Shimoda is a small fishing port and

resort town set at the southernmost tip of the Izu Peninsula. It has the sleepy

holiday-feel of a seaside town. We wandered round its narrow streets, finding

an ashi onsen (natural foot spa), where

we could dip and ease our aching feet after our day long hike.

We later saw a second snake slithering down the side of an old wooden house beside a small stream. As the snake stretched itself out down the side of a window-frame I was able to gauge that it was well over two metres in length. It dropped into the water and zipped with lightning speed across the channel to the point where we were standing. Both it and we eyed each other warily as it rose up the stone embankment directly beneath us and then disappeared into the undergrowth. Passing by, an old lady out walking her dog asked us what was so intriguing about the thicket at the base of this tree, and when we told her she said there were lots of snakes around this area, and she always talked to them. She said we should do the same, “… because snakes are very intelligent, and they know; so you should always be friendly to them, never afraid, because – they know …”

We later saw a second snake slithering down the side of an old wooden house beside a small stream. As the snake stretched itself out down the side of a window-frame I was able to gauge that it was well over two metres in length. It dropped into the water and zipped with lightning speed across the channel to the point where we were standing. Both it and we eyed each other warily as it rose up the stone embankment directly beneath us and then disappeared into the undergrowth. Passing by, an old lady out walking her dog asked us what was so intriguing about the thicket at the base of this tree, and when we told her she said there were lots of snakes around this area, and she always talked to them. She said we should do the same, “… because snakes are very intelligent, and they know; so you should always be friendly to them, never afraid, because – they know …”

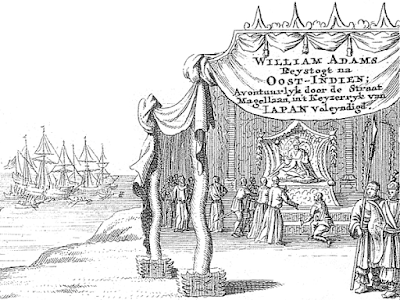

Shimoda is perhaps most famous for

its association with three westerners: Samurai William, Townsend Harris,

Commodore Perry and his ‘black ships.’

William Adams (1564-1620), is actually

more closely associated with the nearby port of Itō, but he is remembered locally as ‘Anjin’ (meaning “pilot”) as he

was a seafarer – an Englishman, originally wrecked off the coast of Kyushu in

1600. He was a navigator and as such he found favour with Tokugawa Ieyasu, the

future first Shogun of Japan’s Edo Period. He counselled Ieyasu on matters of

western mathematics, navigation, and armaments. In return he was granted

samurai status and given his own estate in Miura, near Yokosuka. It was at Itō, just up the coast, that he

constructed and launched Japan’s first western-style fleet of ships. Adams

himself sailed on diplomatic missions to places such as China and the

Philippines on behalf of the bakufu 幕府,

or Shogunate government. One of these ships was even believed to have sailed as

far as Mexico.

Much later Commodore Matthew Perry

(1794-1858) arrived in Japan to a very different kind of welcome. For much of

the Edo Period, under the Shogunate, Japan’s borders had remained firmly closed

to outsiders, but the arrival of Perry in 1853 was to force a change to this

policy. An American, Perry and his small force of soldiers negotiated a “Treaty

of Friendship” that opened the way towards establishing trading rights for a

small enclave of foreigners which later grew up at Shimoda before eventually

moving up the coast to the more conveniently located Yokohama, not far from

Tokyo itself (which was then known as Edo at that time).

Townsend Harris (1804-1878) arrived

in Shimoda in 1856 as the first American Consul to Japan. The controversial

story surrounding Harris is still unclear, yet the bare facts seem to be as

follows. Harris was a rather puritanical bachelor in his mid-50s who suffered

from stomach ulcers. Local officials are said to have prevented a beautiful

young girl of 17 years old, Saito Okichi, from marrying her intended fiancé and

instead ordered her to attend to Harris – it is unclear exactly in what

capacity this was originally meant to be, either as nurse, maidservant, or

possibly as concubine; and it is also unclear if this was of the officials’ own

doing or if they’d been prompted to it by a request from Harris himself. Either

way Okichi was renowned locally for her beauty, and, as such, rumours soon

arose regarding the nature of her association with the American. Tragically,

whatever the truth of the circumstance, she remained tainted by this

association long after Harris had left Shimoda, and consequently she eventually

turned to drink. She did later marry her fiancé but because of her drinking he

later divorced her. She tried to open a restaurant in Shimoda, but it failed

soon after. She was later partly paralysed by an alcohol-induced stroke, and

eventually in 1892 she drowned herself in a local river. There is now a small

museum dedicated to Townsend Harris and the unfortunate Okichi. A small

festival is also held every year in her memory. However, a different story has

it that Harris dismissed her after just three days.

The waterfront of the town is

dotted with several memorials to Perry and his kurofune 黒船, or ‘black ships’, as well

as monuments to Japan and the United States’ continuing diplomatic alliance and

friendship. Yet wandering around the docks area of Shimoda I was more minded of

the elegiac image at the end of Kawabata’s short story in which the student

narrator departs for Tokyo by boat. He looks back to see the little dancer

girl waving a white handkerchief. He can no longer make out her face across the

distance, but he continues to watch as she waves him farewell. Izu is certainly

an enchanted, and, equally, an enchanting place. Like the story of “The Dancing

Girl of Izu” my memories of this trip will stay with me forever. A lingering,

long-remembered set of lost images and feelings, framed within the warmth of my

heart.