I recently attended the launch

events of two newly published books relating to the Himalayas. Although the two

books focus on different countries they tell two similar tales concerning the

regretful demise of two nominally independent Himalayan states – Tibet and

Sikkim.

As the high era of Western

Imperialism in East Asia was drawing to a close in the first half of the twentieth

century many of the different polities in the region were vying to maintain or

establish international recognition of their own sovereign legitimacy. In the

wake of US President Woodrow Wilson’s speech of 11th February 1918, advocating ideas of

national ‘self-determination’, and the active

indigenous intellectual project of envisaging a future post-colonial

era, this struggle for sovereignty meant that many smaller states and

former protectorates found themselves precariously over-shadowed by their larger and more

powerful neighbours.[1] Sikkim and Tibet being two distinct examples.

|

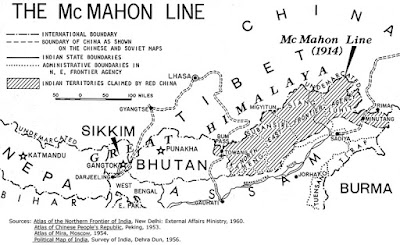

| In 1913-1914 the Simla Conference attempted to establish international boundaries between British-India, Tibet and China |

The boundaries of such

polities had always been rather vague in Western terms. Not so much represented

by lines on accurately surveyed maps, but rather delineated by a complex,

web-like skein of distinct social, cultural, political, economic, and religious

ties. During the long period of British administration in India, the Himalayan

states to the north, despite being perceived as peripheral regions, nonetheless,

were keenly watched as regions of great strategic importance, increasingly

becoming the source of much imperial anxiety. In the so-called ‘Great Game’ of

contesting empires the British had always looked warily towards these Himalayan

states and repeatedly attempted to cultivate or coerce them, attempting to establish

them as a kind of politically amenable ‘buffer’ zone between India, Russia, and

China. But later, with the Russian Revolution of 1917, the withdrawal of the

British from India in 1947, and the Chinese Communists finally securing control

after a protracted civil war with the Chinese Nationalists in 1949, the immediate

post-World War 2 era witnessed a new realignment of the geopolitical scene.

India, the USSR, and China each jockeying for the consolidation of power and

influence within the region.

Surveys & Explorations - Himalayas & Central Asia, 1934

In 1950 the newly

established Communist Government in China announced that the People’s

Liberation Army, having secured the Chinese mainland, would now turn its

attention towards the ‘liberation’ of Tibet from its long established feudal form

of monastic government, and thereby bring Tibet firmly back into the Chinese fold.

Meanwhile, in Sikkim the ruling Chogyal – aware that he was no longer protected

by the former British system of administration in India – sought to establish

and assert the legal status of an independent Sikkim along the same lines as

those already recognised with respect to the neighbouring Kingdoms of Nepal and

Bhutan.

Yet, as these two books clearly demonstrate, neither situation was to

end happily for those who considered themselves independent Tibetans or

independent Sikkimese.

Tibet: An Unfinished Story

By Lezlee Brown Halper & Stefan Halper

(Hurst, 2014)

To mark the launch of Tibet: An Unfinished Story the book’s publishers, arranged an interesting discussion

which brought together one of the book’s authors – Stefan Halper, with noted

journalist and China Correspondent, Isabel Hilton, and Sir Richard Dearlove,

former Head of the British Intelligence Service.

The discussion ranged across

the book’s main themes, examining the current situation in ‘Xizang’ or the

‘Tibet Autonomous Region of China’ and the diplomatic impasse between the

Chinese Government, His Holiness the Dalai Lama, and the Tibetan Government-in-exile

in Dharamsala, India. The authors are both academics based at Cambridge

University, and Stefan Halper also previously served in the White House and the

US Department of State, which meant that the discussion regarding today’s Tibet

was a distinctly political one, covering a lot of highly contentious themes – not

least the disappearance of the 11th Panchen Lama, aged just 6 years old in 1995

(which Isabel Hilton has herself written about[2]), and the recent rise in protests by

ethnic Tibetans, particularly in the form of self-immolation, against the present

system of Chinese administration within Tibet which is widely criticised as

being stiflingly repressive.

The discussion did also seek to place the

contemporary situation within a broader historical context, whilst continuing

to look to the future, not least given the uncertainties borne of the recent

changes occurring in China’s increasing economic engagement with the wider world;

speculating how China’s outlook may begin to change as it continues to open up

as part of its continuing ‘peaceful rise’ as a burgeoning new global

‘superpower.’

In this light, rather than

being an overarching history of Tibet, this book is primarily focussed upon an

analysis of United States' Foreign Policy towards Tibet and India, specifically

in the period after the close of World War 2. It examines in detail Henry

Kissinger and Richard Nixon's diplomatic engagement with the People's Republic

of China in the 1970s. The role of India’s first Indian Prime Minister, Jawaharlal

Nehru, also forms a pivotal focus for much of the central portion of the

text. The book does very briefly attempt

to situate this period in relation to Tibet's long and remarkable history prior

to this time (and concludes by giving some comment on recent events, for

example – the unrest during the 2008 Beijing Olympics), but, it’s fair to say

the authors deftly manage to cover this long and complex early phase of Tibet’s

history in a rather slim set of pages at the start of the book, giving just

enough detail to adequately reach its main period of focus which it then

examines in much closer detail. In this sense, as might be expected given the

authors’ backgrounds, Tibet: An Unfinished Story is essentially a political

history of US diplomatic relations with Asia (and the CIA’s covert activities

and involvement with the Tibetan-Khampa armed resistance effort) during the

height of the Cold War era.

Uncompromising in its

sympathy for the cause of Tibetan independence, whilst acknowledging that this has to

a certain extent been mythologised as a perpetual ‘Shangri-La’ by an otherwise effectively

disengaged West, this book is nonetheless a thoroughly researched and firmly grounded

academic analysis – utilising both US and Chinese sources – to examine a deeply

contentious and emotionally complex history.

Sikkim: Requiem For A Himalayan Kingdom

By

Andrew Duff

(Birlinn, 2015)

An article in Time magazine

published in 1959 observed that: “What

happens in Tibet has always echoed in Sikkim.”

Sikkim: Requiem for a Himalayan Kingdom by my friend, Andrew Duff, was published last month. The book

begins as a simple travelogue in which the author embarks upon a trek through

Sikkim to retrace the footsteps of his Grandfather, who had journeyed through

the region in the 1920s, but a chance meeting with a monk at Pemayantse

Monastery prompts Duff to delve deeper into the more recent history of this tiny

former Himalayan kingdom. The compelling story which follows is essentially a

political-biography of Sikkim’s 12th and last Chogyal (or King), Palden Thondup

Namgyal, whose life was entirely dedicated to the struggle to maintain the

semi-independent sovereignty of his native kingdom in the wake of the British

withdrawal from empire in India in 1947.

In 1890, during the time of

the British Raj, Sikkim had become a protectorate of the British Empire, a

status which was nominally maintained after India gained independence and later

affirmed in a treaty signed in 1950 with the Indian Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru.

As a suzerain state, Sikkim remained administratively autonomous whilst

transferring control of its external affairs, defence, diplomacy and

communications to India. Yet Sikkim could not escape the ever looming shadow of ‘Great Game’ machinations which continued between its larger neighbouring

states. Diplomatic relations between the USSR, India and China – particularly

after the Chinese took control of Tibet in 1950 – continued to remain fragile,

and this air of uncertainty only seemed to heighten the geopolitical anxieties

concerning the somewhat nebulous mix of different ethnic polities which reside

in what was still very much perceived to be a highly vulnerable Himalayan

border zone. Unlike neighbouring Nepal and Bhutan, which were both able to

establish their own independent sovereignty in the eyes of the international

community, Sikkim was essentially out-manoeuvred by political forces operating

both within and outside its borders.

A discontented faction

within Sikkim itself – lead by the Kazi and Kazini, Sikkim’s Chief Minister and

his indomitable Scottish wife – increasingly began to agitate against the power

of the Chogyal, pressing for a more democratic system of government. The

Chogyal, relying on the support of the Indian Government, initially resisted

but eventually reluctantly conceded to certain changes which began a process

that gradually eroded the political influence and control hitherto vested

solely in the monarch. But, in the long run, each of these parties was

essentially out-manoeuvred by the Indian Government, under Nehru’s daughter,

Indira Gandhi, who essentially very carefully laid the groundwork for a coup

which was later staged by the Indian military in 1975. A referendum followed suspiciously

swiftly in which a majority reportedly seemed to be favour of Sikkim

relinquishing its sovereignty to become a state within India proper. Even

though the anti-Chogyal faction and the monarch managed to come to an agreement

at the eleventh hour it was too late, each had fallen foul of the duplicity of

Indira Gandhi’s officials operating within both Sikkim and Delhi.

Despite keeping a keen eye

on the sequence of events and confusing political developments taking place

within Sikkim, officials in the US and the UK could offer little beyond

sympathetic platitudes, whilst China and Pakistan used the situation as a

rhetorical lever, as and when it suited their purpose, either to condemn India or absolve their own parallel actions

in other contested regions. Sikkim was sadly seen as simply too small a pawn in

the international politics of the region for its former friends and allies to

be of much help in preserving its autonomy. Whereas Tibet had lost its autonomy

under duress by direct force, as Duff demonstrates, Sikkim had somewhat

unwittingly been progressively hoodwinked by a war of political stealth and attrition.

Andrew Duff very ably

reconstructs the machinations of this era using a variety of sources and

archive material, drawing in particular on the richly personable papers of two

westerners, both women missionary school teachers from Scotland, who each lived and worked

for a number of years in Sikkim throughout this turbulent period, and both of

whom were close to the Chogyal and his second wife, the American Hope Cooke.

Their marriage was originally a glamorous, oriental fairy-tale romance, reminiscent of

American actress Grace Kelly and Prince Rainier III of Monaco, but which

eventually fractured under the personal and political strains of Sikkim’s

struggle. Ultimately Sikkim: Requiem for a Himalayan Kingdom is the story, engagingly told, of the tragedy

which befell a colourful cast of individuals caught and completely churned over

in the tumultuous wake of competing Cold War era leviathans thrashing out a new

international order in the immediate post-colonial fallout of the mid-late twentieth

century.

Read

an interview in which Andrew Duff discusses Sikkim on the Asia House website.

~

Read my review of Karl E. Ryavec's 'A Historical Atlas of Tibet' (University of Chicago Press, 2015) on the LSE Review of Books website.

~

Read my review of Karl E. Ryavec's 'A Historical Atlas of Tibet' (University of Chicago Press, 2015) on the LSE Review of Books website.

[1] See, Erez Manela, The

Wilsonian Moment: Self-Determination and the Origins of Anticolonial

Nationalism (Oxford University Press, 2007)

[2] See, Isabel Hilton, The Search for the Panchen Lama (Norton, 2001)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments do not appear immediately as they are read & reviewed to prevent spam.