In 1800 Napoleon Bonaparte crossed

the Great St Bernard Pass with his 40,000 strong army. A heroic feat which

certainly appealed to the contemporary Romantic imagination of the time. Like

Hannibal and Charlemagne before him, he was a modern embodiment of ‘a superhuman power pitted against the

supernatural terrain.’ The feat, and the man himself, were immortalised in

Jacques-Louis David’s contemporary portrait – Napoleon on the St Bernard Pass.

Yet only two years later, in 1802 –

during the brief Peace of Amiens – a different painter actually made the same mountain

crossing for himself. Only 27 years old at the time, but already at the top of

his profession and widely regarded as the most outstanding British landscape

painter of his generation, J.M.W. Turner was travelling on his first tour of

continental Europe. In later years, unlike his contemporary countryman, the

landscape painter John Constable, who never left Britain at all, Turner became

a frequent traveller in Europe. Despite a poor aptitude for foreign languages

Turner’s confidence was ever undaunted. His first tour, travelling in style in

the company of an aristocratic patron, must have set the pattern – even though

subsequent trips were made alone and as cheaply as possible. Turner’s unabashed

adventurousness was perhaps matched only by his natural curiosity and his

artistic acuity – the body of works he created whilst on this first Alpine tour

is regarded by critics as peerless.

According to David Blayney Brown, “No painter before Turner, and none since, has

so truly grasped the wilderness and grandeur of the mountains, their beauty,

their savagery and their tragic loneliness. And here, of course, he left the

Grand Tourists far behind. They had hurried through the Alps to acquire polish

and sample the pleasures of Italy, but for Turner they were an education in

themselves, confirming – if confirmation were needed – his commitment to the

art of landscape, and raising his conception and techniques to new heights.”

It’s thought that Turner probably

saw a version of Jacques-Louis David’s epic portrait of Napoleon sat astride

his rearing steed atop the St Bernard Pass when passing through Paris. And it is

certainly appealing to speculate, as Blayney Brown does, that in retracing the

same arduous mountain crossing, Turner “…

doubtless heard local stories from the guide of the real details of the 1800

crossing – how Napoleon had based himself in Martigny directing supplies before

rejoining his men, or sent the monks at the Great St Bernard hospice rations to

feed the troops when they arrived – and as he scrambled over the pass, would

have realised the extent of David’s flattery and fiction. Did he, as he passed

through Bourg-Saint-Pierre on his descent through the Val d’Etremont towards

Martigny, learn how a peasant from the village had guided Napoleon over the

pass, on a mule and in the rear of his army – so different from the heroics of

David’s canvas? It would take ten years, a snowstorm in Yorkshire and the

hubris of Napoleon’s Russian campaign before Turner felt able to deflate such

myth-making in the greatest of his Swiss pictures, ‘Snowstorm: Hannibal and

his Army Crossing the Alps,’ reducing the

ancient Carthaginian to whom Napoleon was often compared to invisibility in an

apocalyptic mountain blizzard.”

Snowstorm: Hannibal and His Army Crossing the Alps, 1812

I like this notion of the very

ordinary Mr Turner as the leveller of tyrants. Deftly underlining the genuine

measure of man against the reality of nature and the power of the elements,

grounded in his deeper, practical understanding and his geographical knowledge

of the locale. This is informed, and intellectually expressed, anti-propaganda

of the subtlest order. That said, though, it’s interesting to note another

painter, Paul Delaroche, whom I very

much admire, was later commissioned to paint a more realistic scene depicting

the crossing. This version, clearly echoing David’s, was not meant to be

demeaning, however, as Delaroche apparently admired Napoleon.

Last year I visited Martigny twice,

in winter and in summer. It is a small town, which dates back to at least the

Roman era (when it was known as Octodurus or Octodurum), tucked away in a steep

sided valley a short distance from the far eastern end of Lake Geneva, not far

from Mont Blanc – an ancient crossroads town with roads leading off to Italy

and France, as well as other parts of Switzerland. I was working at the

Fondation Pierre Gianadda, an art gallery whose grounds incorporate several

Roman ruins amidst a fine collection of modern art sculptures.

A little way down the road stands

the remains of a very fine Roman amphitheatre. Overlooking the town is La Bâtiaz, a small fort with a high

tower, which gives commanding views along the valley whose slopes are covered

with terraces laced with carefully cultivated vines. The wines of the Valais

region are, in my carefully considered (and equally savoured) opinion, one the

best little known secrets of Europe. Martigny is very proud of its heritage – and

certainly of its connections to famous artists such as Turner, plus poets and

writers, like the Shelleys and Lord Byron, who all passed through here; perhaps

unsurprisingly, though, less mention seems to be made of his nibs, ‘Old Bony’ –

Napoleon Bonaparte.

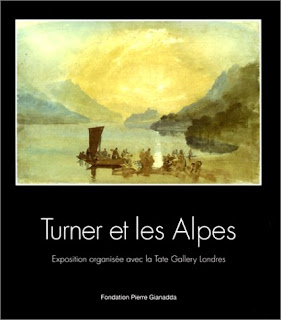

In 1999 the Fondation Pierre

Gianadda, in collaboration with the Tate Gallery in Britain, hosted a wonderful

exhibition, titled: Turner et les Alpes. It

was a real pleasure to leaf through the catalogue for this exhibition, and to

compare it to the vistas which greeted you whilst walking around the town,

almost as it were as if one was peering over Turner’s shoulder in some places –

seeing him sketch out the scene in one of his sketchbooks, which were later

worked up into finished watercolours – like a window into his past.

Further Reading:

David Blayney Brown, Turner et les Alpes, 1802 (Fondation

Pierre Gianadda, 1999)

David Hill, Turner in the Alps: The Journey through France & Switzerland in

1802 (George Phillip, 1992)

All images of artworks, The Tate Gallery, London; except the two paintings of Napoleon, Wikimedia (click on images for more info). Photographs of Martigny by me, 2014.

You might also like to read Alex Cochrane's article on Charles Dickens' visit to the Great Saint Bernard Hospice in 1846 - "Dickens: The Frozen Dead and a Macabre Swiss Mortuary"

Also on 'Waymarks'

Fascinating...glad I caught-up with this. Anything with Turner can't fail! Thanks for link and reciprocated in my article - Alex

ReplyDelete