Part X

“I

would like to try to deal with some of the more intimate and personal aspects

of travel. They may be trivial or absurd, but one must remember that in a few

years, most of our existing methods of transport, together with the physical

and mental emotions that accompany them, will be profoundly changed. The time

is near when men will receive their normal impressions of a new country

suddenly and in plan, not slowly and in perspective; when the most extreme

distances will be brought within the compass of one week’s – one hundred and

sixty-eight hours’ – travel; when the word ‘inaccessible’ as applied to any

given spot on the surface of the globe will cease to have any meaning.”

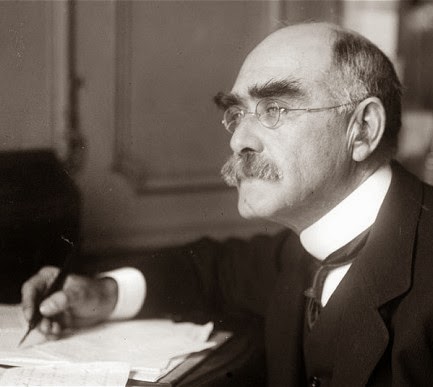

These words were spoken a little

over a hundred years ago by Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936) in an address to the

Royal Geographical Society in London. The exact date was the evening of

February 17th 1914.[1]

When reading travel accounts from this era I’m often struck by how remarkably

forward looking they are; something which is notably in contrast to similar

travel accounts published in our own time, which often strike me as being

rather more nostalgic. Perhaps it was a characteristic of the age of Western

imperialism? Notions of modernity infusing a sense of purpose and a sense of

faith in human progress. Boundaries were busily being pushed back. Frontiers

were falling. The project of globalisation was proceeding apace. And now, in

our own era, when that project has perhaps faltered or reached some sort of

equilibrium, faced with newly dawning uncertainties, what else can we do but

look back? [2]

Commenting on Kipling’s talk that

evening, Lord Bryce (1838-1922) – who was asked by Lord Curzon (1859-1929), the

President of the RGS, to express the meeting’s thanks to Kipling – he continued

the observation quoted above with which Kipling opened his talk: “If any of you are inclined to envy the men

and women of the future who will be able, in the course of an afternoon to

reach the United States, and South Africa to-morrow morning, and to wish that

you had been born in those days, let us comfort ourselves with the thoughts

that at those heights which the airships will traverse, there will be no

colours of landscape to enjoy, for colour fades out of things when you pass

over them at a height of 5000 or 6000 feet. Neither will any scents reach the

future high-level travellers. So let us come back to the old conclusion that we

may be well content with the world in which we live, even if it be not the best

of all possible worlds.”

One can’t help wondering what Lord

Bryce would have made of the realities of travelling long-haul economy class at

35,000 or 36,000 feet (!) today – with the blinds all pulled firmly down in

accordance with the cabin staffs’ instructions, and everyone with headphones on,

plugged into their TV sets and tucking into their in-flight meals, whilst

assailed by the stifling dryness and the occasional odd aromas circulating in

the recycled air of the closed cabin (Kipling’s talk had made a point of

emphasising the evocative nature of smell as a distinctly remembered

characteristic of travel). Perhaps this shows that some people a hundred years

ago had a clearer vision of ‘human progress’ than others! I don’t suppose Lord

Bryce would have been a fan of modern air travel – for all its gruelling convenience,

how many of us in our hectic and evermore time-pressed lives can conceive of

the same journey taken by steamer over weeks through both choppy seas and fine

weather? How does our experiences of turbulence compare to a howling gale on the

water? Or the spun body-clock of jetlag to the forced idleness of days spent in

a cabin or strolling the promenade deck with nothing but a desolate expanse of

water to meditate upon?

Travel is always an experience.

Often travel is defined by its modes of transport as much as its duration, and by

our company too – all these elements essentially combine. In the early 1990s I

went on two separate student exchange trips to the newly re-unified Germany.

For the first of these we travelled out from the UK overland by bus, for the

second we flew. On the first we had a two day trip before we reached our

destination in which to get to know one another better than we previously had

in the normal day-to-day routines of our school life, and consequently it

induced a tight knit camaraderie which transformed our subsequent stay in

Germany. On the second exchange trip a few years later, which was made with a

different group of students at a different school, we were very much flung

instantly into our new situation overseas in a much more immediate and isolated

sense as the flight lasted less than two hours. An hour in the departure hall

wasn’t enough time to make us feel like the solid intrepid band which had been

forged and united by the previous bus and ferry ride across the Channel and the

autobahn to Germany. In a similar way

my trip to 康定 Kangding (དར་རྩེ་མདོ། Dartsendo) was defined by the effort

required to reach the town.

It took only a few hours to fly

from Shanghai to Chengdu, but (on average) an eight hour bus ride out to

Kangding and the same back again – a journey which a hundred years ago would

have been made over a number of days and mostly on foot. Reaching Kangding

really felt like reaching somewhere partly because of the effort required and

partly because it is still quite an ‘out of the way’ sort of place, not quite

altogether off the beaten track but still comparatively speaking fairly remote.

Here though, I was travelling

alone. There were only a handful of other Westerners staying or living in

Kangding. Most of the travellers (as we were all independent travellers rather than

package tourists) were holed up at one of either two hostels, and a lot of

these seemed to be just passing through or taking a couple of days’ break to

catch up with laundry and internet. I spent a lot of time wandering around the

town, with a sheaf of old photos printed out from my computer, trying to match

old views to the present, seeking to orientate myself and get my bearings,

piecing together an old version of Kangding which had long since been

transformed, buried, or disappeared. Every now and then I’d find a former trace

of that past place, and as such a little more of the history which I’d either

heard or read about from family, or books or archives would fall into place.

But reflecting on this now, it wasn’t so much the cliché of bringing history to life – it was more

like a process of conjectural surveying and factual mapping. In my mind I was

constantly pegging reference points and trying as best as I could to connect

them together to form a clearer understanding. Continually stopping to remind

myself that it was easy to make assumptions and that one should always qualify

oneself with the thought that an idea or link could later prove incorrect or

wrong.

Trying to place the old French

Catholic Church was a case in point. Having climbed a flank of one of the

hillsides overlooking the town to a precarious vantage point I managed to

convince myself that the location of the old church might well have been on the

site of the present one (which on the face of things seemed logical enough) –

yet later on it became apparent from carefully scrutinising another

photographic source that the geography of that particular theory was probably

all wrong; as such, seen from a different angle, the old church was more likely

to have been situated on the other side of the river and further downstream

(perhaps near where the modern town square or piazza is presently located?). As

with a lot of these types of thing, it’s probably hard to ever be certain.

Something I’ve yet to come across

is any old, officially printed or even roughly sketched maps of the town’s

former layout. But that’s the point of research, you never really give up – you

keep looking, and you keep your mind open to revising your findings in the

light of new discoveries. As with my last stroll along the Lu Ho Valley,

there’s always the lure of that next bend in the road or rise on the horizon,

tempting you ever forward, wondering what you might find just around the

corner. The difficulty and perhaps the greatest sadness is deciding when to

stop and draw a line. Maybe you’ll decide to keep travelling forever, or maybe

others travelling with you or after you will take your journey further – but in

the end, that is something which only time will tell.

Such journeys aren’t all about the

past though. Our notions of history say as much about the present as they do

about the reality of the past. It’s a fascinating angle to explore the here and

now as much as it is to seek out the past. Chatting to Mr and Mrs Lao in their

front room; or being welcomed in by Tibetan monks eager to practice their

English with an interloping foreigner; or being hijacked and lead on a happy,

whirlwind tour of a lamasery by some local children – for whom the lack of a

shared language didn’t seem to be any sort of a barrier; or, similarly, being

invited to take shelter from the mountain rain in a farmer’s house and managing

to use my battered old Japanese/Chinese/English vocab’ book to communicate with

him and his family over copious cups of hot tea and warm natured smiles. All of

these experiences combined to make my own trip to Kangding a memorable and

personally rewarding one. I found much more than I’d dared to expect travelling

to Kangding, and, as such, I hope it will in time prove to be but the first of

several – perhaps longer – trips yet to the town and the regions beyond.

This

is the last in my series of posts on my 2010 research trip to Kangding

(Dartsendo). I will occasionally write other posts related to my research, upon

the lives of Rinchen Lhamo and Louis Magrath King, as well as the broader topic

of my PhD which will be focussing on Western travellers in East Tibet in the

early 20th century and the theme of ‘science and imperialism.’ These

will all be listed and linked under the ‘research’ tab at the top of this blog.

If anyone would like to post comments on the blog or contact me directly to discuss these

topics or my research I’d be most grateful to hear from you.

[1]

See: The Geographical Journal, Vol.

XLIII, No. 4 (April, 1914), pp. 365-378

[2] I

think there’s the germ of an idea for a paper waiting to be written here!

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments do not appear immediately as they are read & reviewed to prevent spam.