Four

Guineas by Elspeth Huxley (first published 1954) is a

colonial geographer's guide to West Africa, written with a journalist's eye

leavened by a certain degree of philosophical self-reflection. Not so much a

travelogue as a gazetteer, tallying the accounts of British taxpayer's

financial contributions to the "civilising mission" of empire in a

"benighted land."

The book describes Elspeth Huxley's personal view, as she sees it, of an

ancient continent without art or culture (except for the inexplicable

'anomalies' of Nok, Benin and Ife), of 'ju-ju' cults and tribal societies mired

in blood feuds and lingering rumours of (once prolific) human sacrifice, seen

askance from the diligent efforts of colonial district officers and

missionaries, toiling in the opposite direction, setting up schools and

hospitals; alongside rising local and national political institutions,

struggling in their infancies. The author's eye and voice is ever present in

these pages, but the author oddly isn't. The text manages to stand at one

remove from both of these opposing 'realities' of Africa. But ultimately

Huxley's purported objectivity is opaque, a thin veneer over the surface of

things as seen en passant.

Whilst Four Guineas seeks to immerse the reader in the daily

life of West Africa the book constantly circles back upon itself and betrays

Huxley's self-affirming (if at times jaundiced) view of Britain's imperial mission

- and this makes it a hard book to navigate, a tough read in some respects, now

some 70 years on from its original time of publication. Oddly dry and

redundantly academic, but with flashes of life and wit appearing every once in

a while, usually as a terminal flourish to each chapter. Although, more often

than not, that wit is witheringly ironic and condescending, occasionally racist

in places. And yet, Huxley has a keen eye and a sharp pen when it comes to the

inequities, physical harm and misogyny experienced by African women.

It's a strange book. Neither wholly a champion nor a detractor of empire,

Huxley isn't exactly an apologist either, though her attempts at being an

objective observer tend to veer in that direction. Four Guineas casts

an eye into a particular time and place, both consciously/unconsciously couched

in a particular contemporary mindset - it gives a window into a colonial world

in its twilight phase, pondering the onset of the post-colonial at its cusp;

and as such, it perhaps remains a valuable historical document for that fact in

and of itself alone, as the following two quotes from the book's closing pages

may help to illustrate:

"A new troubling tide - that is what we are, we Westerners, a tide that

has stirred the deposit of centuries. Tides, by their nature, recede. In one

sense we are already in recession; as the ruling power, Britain is everywhere

disengaging her grip. The speed of this retreat is indeed phenomenal, and much

greater than it needs to be if Britain's work is to endure. As it is, the time

has been too short to lay secure, or even rudimentary, foundations. Yet, had it

been prolonged, the ill-will engendered by sloth in abdication - once

abdication had been proclaimed as the objective - would so have inflamed and poisoned

the body politic that Britain's constructive task would have become impossible,

since rifles do not promote racial harmony. This was Britain's dilemma, which

she solved by deciding to hurry quickly and risk the results." p.312

"It sometimes appears that our modern colonies are forcing-houses where,

under conditions of great heat and sultriness, we cultivated transplanted

seedlings in soil deficient in certain ingredients needed for the healthy

growth of those particular exotics. We force an omnipotent bureaucracy without

honesty, a democracy without enlightenment, an economy without toil, a nation

without unity, a culture without art: in short, a society without faith to give

it purpose or a code of morals to give it strength. Strange blooms may result."

p.313

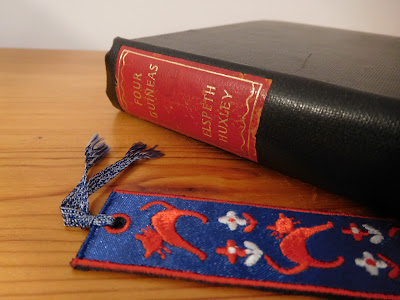

[My copy is The Reprint Society (London, 1955) edition]

|

| Elspeth Huxley, 1907-1997 |

Elspeth Huxley was born in England in 1907 to British parents, Nellie (née Grosvenor, daughter of Lord Stalbridge) and Major Josceline Grant, who became colonial settlers in Thika, British East Africa (now Kenya) in 1912. Growing up on her parent’s coffee plantation, Elspeth began her somewhat sporadic education at a 'whites only' school in Nairobi, and then briefly at boarding school at Aldeburgh in Suffolk from which she was expelled for gambling on horse racing. In 1925 she returned to England in order to study agriculture at Reading University, then in 1928 she continued her studies in the USA at Cornell University. After which she worked as an assistant press officer at the Empire Marketing Board, and then subsequently as a broadcaster for the BBC during the 1940s and 1950s, specialising in African affairs. She also served as member of the Monckton Advisory Commission on Central Africa (1959-1960).

In

1931 Elspeth married into the famous Huxley family. Her husband, Gervas Huxley,

who had been her boss at the Empire Marketing board, was a cousin of the writer,

Aldous Huxley. She was also a friend of Joy Adamson, author of Born Free

(1960), which is perhaps more widely remembered because of its film adaptation

and the popular song of the same title. Elspeth’s own writing career was long

and prolific. She began as a teenage journalist, writing for various newspapers

and magazines in Africa. Publishing her first book in 1935, she subsequently

authored more than forty books of both fiction and non-fiction – Africa forming

the common theme and backcloth to her novels, memoirs, travelogues, and commentary works. Perhaps

naturally her colonial background, her education, and her work for British

imperial institutions shaped and influenced her outlook which was initially very

pro-colonial, but she later came to support contemporary moves towards African

Independence, as Four Guineas attests. In this respect, whilst some of

her personal attitudes have become outmoded, her polemical writings still stand

as interesting insights into, and valuable eye-witness accounts of changing

colonial attitudes regarding the political, economic, environmental, and

cultural issues which were widely salient across the African continent during

the mid-late twentieth century.

Four

Guineas is perhaps not one of her better-known works, such

as The Flame Trees of Thika: Memories of an African Childhood (1959) and

The Mottled Lizard (1962), autobiographical reflections

upon her life growing up in Kenya which have been criticised as describing a

rose-tinted view of colonial Africa and providing an apologia for colonial

rule. Her books, however, also reflect a deep and often empathetic interest in the

cultures of the Masai and Kikuyu peoples, which she had previously written

about in her novel, Red Strangers (1939). When it was first submitted to

the Macmillan publishing house, the unflinching descriptions Red Strangers

contained of female circumcision rites were said to have made Harold Macmillan

(who later became British Prime Minster) blanche, but refusing to compromise on

editing such passages Huxley took the book to Chatto & Windus instead, who

published it with less qualms. A recent reissue of the book by Penguin Classics

was supported by the polemical scientist, Richard Dawkins, who himself was likewise born and raised in colonial

Kenya. Dawkins also wrote a preface to the new edition.

In

1962 Huxley was awarded a CBE for her writings on Africa, and she continued

writing on these subjects into the 1990s. Elspeth Huxley died in England in

1997, aged 89. In an obituary, The New York Times described her as “a

witty and energetic journalist” whose “eclectic literary output

reflected an extraordinary range of interests”, and as a constant supporter

of myriad causes who remained tirelessly “energetic to the end.” It

seems to me she was perhaps a writer of her own era, but also one who reflected

the changes and adaptations of those times, having lived through an epoch in

which the world experienced a massive and rapid cultural shift of global

proportions. Through her contemporary commentaries she perhaps unwittingly gave

us a ‘history of the present’ as she and her contemporaries saw it in real

time; a worldview which we might no longer share in its narrowness and its

self-inflated suppositions, but one which we could certainly benefit from

studying and understanding in order to broaden and better our own.

Also on 'Waymarks'

Dan Eldon - "Safari as a Way of Life"

Temples & Feluccas - Travelling in Egypt

Challenge in Nigeria, 1948.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments do not appear immediately as they are read & reviewed to prevent spam.