I recently finished reading Edmund Candler’s The Unveiling of Lhasa (Thomas

Nelson, 1905). What follows are my first impressions and reflections linking a

selection of passages from that text (these centre on themes which I aim to

expand upon in my PhD thesis).

On the whole I found the book a

curious mix. For the most part it is an unpalatable, almost surgical recounting

of the military conquest of Tibet. A lot of people die in these pages, and it

is hard not to baulk at the fact that the objectivised recounting of these

‘facts’ are not a fiction. These events occurred. The (at times) Boy’s Own adventure-style is deeply

apparent. This unfortunate event is perhaps the last 19th

century-style military Imperialist incursion of the British Empire. It is couched

as a heroic “last hurrah”, as Tibet represents a final blank space on the world

map. Somewhere to be claimed and conquered. Civilisation pitted against

savages. The book overflows with orientalising

tropes, and yet there are moments of poignant detachment – when moral

reflections are countenanced, but often subsequently dismissed or explained

away in the end. What happened, happened. And it happened for a reason; because

it had to happen. And what’s done is done, and henceforth the world (and the British

Empire) will be a better place because of it. A triumph for the “geniuses” of

Empire (in this instance, those geniuses are Sir Francis Younghusband, leader

of the military expedition, and Lord Curzon, Viceroy of British-India).

|

| Sir Francis Younghusband |

The “Unveiling” of the book’s title is telling. Candler’s tone hints

at all the inevitable metaphors. The Younghusband Mission of 1904 ends in a marriage of sorts, but it is a shotgun

wedding (without any metaphor). A military force enters Tibet, penetrating the sanctity of its holy and forbidden capital city, with murder and

plunder marking every painful step of its march. This book reeks of Freudian

psycho-babble. But its main thrust is the moral reasoning of a marriage of

medievalism with modernity. Tibet is a backward, feudal anachronism which has

violently awoken to the realities of modern Western civilisation. All the way

from the Chumbi Valley to Lhasa the British have tried to reason and negotiate

with the benighted and duplicitous Tibetans, but their stubborn obstinacy time-and-again

has forced the British hand. It is a cultural clash of misunderstandings which

can only be overcome by the power of the Maxim gun. Despite the devastating

mechanised firepower employed it was touch and go at times, when the “enemy”

missed glaringly obvious opportunities to cut off the British line of supplies.

There’s little thought evident in Candler’s narrative that the Tibetans might

have been fighting (i.e. – defending themselves) under different terms, and

with a contrasting conception of the rules of engagement.

Reading these decidedly one-sided

pages one can’t help but be aware of the deafening silence of the other side. Many

of the British soldiers (officers, certainly) are named, whereas the mass of ‘natives’

– both Sikh and Ghurkha friend and Tibetan foe – are not. I kept thinking of

the Spanish Conquest of the Americas. And this is a point which Mary Louise

Pratt has used to good effect in her analysis of such colonial encounters. The

process of transculturation which

takes place in these Western colonial era writings is what interests me too.

These types of books were predominantly written by men of Classical education –

the struggles (agon) and trials

of Homer’s Odysseus and Virgil’s Aeneas soak through their words and redolently

permeate their world outlooks; triumph and victory are won through the defeat

of adversity. Respect is due to those who evince martial honour; and nobility

is conveyed by lofty ideals, upholding reason and the pursuit of higher

knowledge – “science” marches in the bloody hobnailed wake of such incursions.

Thus civilisation simultaneously justifies and obfuscates its own barbarism;

turning the tables on itself, expiating and exculpating all its blinkered ills.

Vide:

– Candler’s dedication of the book:

“These

pages, written mostly in the dry cold wind of Tibet, often when ink was frozen

and one’s hand too numbed to feel a pen, are dedicated to COLONEL HOGGE, C.B.,

and THE OFFICERS OF THE 23RD SIKH PIONEERS, whose genial society is

one of the most pleasant memories of a rigorous campaign.”

It’s all there. Adversity and congenial

company. War, weather, and pleasant conversation with one’s chums.

|

| Younghusband (front row, centre, in fur coat) and Col. Hogge (back row, second from right) at Phari Jong, 1904 |

The rest of the book is at pains to

account for and justify the perceived punitive aims of the Younghusband campaign,

which the Tibetans have in effect only brought upon themselves. Edmund Candler (1874

– 1926) was a war correspondent for the Daily

Mail – an “embedded journalist” in modern parlance – and his book was born

of his original despatches to that newspaper. In essence we could read this

work as tacitly sanctioned propaganda. I’m not sure to what extent his reports

were actually vetted by the expeditionary Force or the British-Indian

authorities, but they could hardly have raised a frown when they read the likes

of the following:

“In

estimating the practical results of the Tibet Expedition, we should not attach

too much importance to the exact observance of the terms of the treaty. Trade

marts and roads, telegraph-wires and open communications are important issues,

but they were never our main objective. What was really necessary was to make

the Tibetans understand that they could not afford to trifle with us. The

existence of a truculent race on our borders who imagined that they were beyond

the reach of our displeasure was a source of great political danger. We went to

Tibet to revolutionize the whole policy of the Lhasa oligarchy towards the

[British-]Indian Government.

The practical results of the mission are

these: The removal of a ruler who threatened our security and prestige on the

North-East frontier by overtures to a foreign Power; the demonstration to the

Tibetans that this Power is unable to support them in their policy of defiance

to Great Britain, and that their capital is not inaccessible to British troops.

We have been to Lhasa once, and if necessary

we can go there again. The knowledge of this is the most effectual leverage we

could have in removing future obstruction. In dealing with people like the

Tibetans, the only sure basis of respect is fear. They have flouted us for

nearly twenty years because they have not believed in our power to punish their

defiance. Out of this contempt grew the Russian menace, to remove which was the

real object of the Tibet Expedition. Have we removed it? Our verdict on the

success or failure of Lord Curzon’s Tibetan policy should, I think, depend on

the answer to this question.

There can be no doubt that the despatch of

British troops to Lhasa has shown the Tibetans that Russia is a broken reed,

her agents utterly unreliable, and her friendship nothing but a hollow

pretence. The British expedition has not only frustrated her designs in Tibet:

it has made clear to the whole of Central Asia the insincerity of her pose as

the Protector of the Buddhist Church.” (pp. 369-371)

|

| Younghusband and the Chinese Amban at Lhasa |

If Orientals are characterised by

their inscrutability, obstinacy and obsession with maintaining “face” – it is

intriguing to notice the parallel Imperialist fixation with “prestige.” The

Great Game represents the higher Imperialist goal, the collective endeavour

from which they derive both means and ends for the projection of power. But it

can belie a different kind of motive which perhaps underlies the individual’s

attraction to and sense of agency within the greater scheme of things. At times

this perspicacity succeeds in peeping through:

“If

only one were without the incubus of an army, a month in the Noijin Kang Sang

country and the Yamdok Plain would be a delightful experience. But when one is

accompanying a column one loses more than half the pleasure of travel. One has

to get up at a fixed hour – generally uncomfortably early – breakfast, and pack

and load one’s mules and see them started in their allotted place in the line,

ride in a crowd all day, often at a snail’s pace, and halt at a fixed place.

Shooting is forbidden in the line of march. When alone one can wander about

with a gun, pitch camp where one likes, make short or long marches as one

likes, shoot or fish or loiter for days in the same place. The spirit which

impels one to travel in wild places is an impulse, conscious or unconscious, to

be free of laws and restraints, to escape conventions and social obligations,

to temporarily throw one’s self back into an obsolete phase of existence,

amidst surroundings which bear little mark of the arbitrary meddling of man. It

is not a high ideal, but men often deceive themselves when they think they make

expeditions in order to add to science, and forsake the comforts of life, and

endure hunger, cold, fatigue, and loneliness, to discover in exactly what

parallel of unknown country a river rises or bends to some particular point

of compass. How many travellers are

there who would spend the same time in an office poring over maps or statistics

for the sake of geography or any other science? We like to have a convenient

excuse, and make a virtue out of a hobby or an instinct. But why not own up

that one travels for the glamour of the thing? In previous wanderings my

experience had always been to leave a base with several different objectives in

view, and to take the route that proved most alluring when met by a choice of

roads – some old deserted city or ruined shrine, some lake or marshland haunted

by wild-fowl that have never heard the crack of a gun, or a strip of desert

where one must calculate how to get across with just sufficient supplies and no

margin. I like to drift to the magnet of great watersheds, lofty mountain

passes, frontiers where one emerges among people entirely different in habit

and belief from folk the other side, but equally convinced that they are the

only enlightened people on earth. Often in India I had dreamed of the great

inland waters of Tibet and Mongolia, the haunts of myriads of duck and geese –

Yamdok Tso, Tengri Nor, Issik Kul, names of romance to the wild-fowler, to be

breathed with reverence and awe. I envied the great flights of mallard and

pochard winging northward in March and April to the unknown; and here at last I

was camping by the Yamdok Tso itself – with an army.

Yet I have digressed to grumble at the only

means by which a sight of these hidden waters was possible.” (pp. 279-282)

Both Candler and his friend,

Rudyard Kipling, wrote with great enthusiasm on the noble endeavour which they

felt embodied the romance of real travel (I’ve written more on Kipling’s views

on travel here), and certainly both men were born and shaped from the

imperialist mould. But Candler was also friends with Joseph Conrad, and Conrad

was a man of a different mind. A novelist, like Kipling, who wrote about empire

– as it was the world in which he lived and operated – but Conrad was Polish by

birth, a seaman who travelled the globe by trade, and eventually a naturalised

Englishman – but one with a distinct distaste for the affects of empire. One

only has to read his eponymous Heart of

Darkness with its pathetic fallacy aptly illustrated by the metaphor of a

naval frigate launching its mighty ordnance into the thick trees of the

jungle-lined coast, the sightless shelling of an unseen foe, which is perhaps only

the impassive and irrepressible verdure of Nature itself. In essence, a futile

act. Conrad best summed up his view of modern Imperialism through the

mouthpiece of his character, Marlow, in Heart

of Darkness:

“The

conquest of the earth, which mostly means the taking it away from those who

have a different complexion or slightly flatter noses than ourselves, is not a

pretty thing when you look into it too much.” (Heart of Darkness, pp. 31-32)

I can’t help wondering – if Conrad

ever read Candler’s newspaper reports from Tibet, or even all of this particular

book, The Unveiling of Lhasa – what

he and Candler would have said to one another in conversation over this topic.

No doubt they saw eye-to-eye on some things, whilst differing over others, as

would many other people existing in the context of those times – but how did

they each think such a world would play out in the long run, and ultimately

might they have been in some sort of accord?

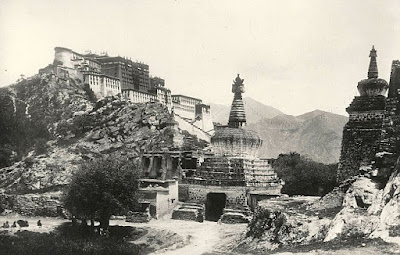

|

| Lhasa, Tibet - 1904 |

References:

Edmund Candler, The Unveiling of Lhasa (Thomas Nelson,

1905)

Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness (first published in Blackwood’s Magazine, 1899;

Penguin, 1989)

Joseph Conrad, Tales of Hearsay and Last Essays (J. M. Dent, 1955)

Mary Louise Pratt, Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and

Transculturation (Routledge, 2008)

Edward W. Said, Orientalism (Pantheon, 1978)

Gordon T. Stewart, Journeys to Empire: Enlightenment,

Imperialism, and the British Encounter with Tibet, 1774-1904 (Cambridge

University Press, 2009)

Also on Waymarks:

Fascinating post of a part of the empire I know little about, but am hardly surprised by as it is a pattern replicated from Sudan to Tibet.

ReplyDeleteEven so, pp. 279-282 ends up being a wonderful requiem to exploration and landscape!

Thanks, Alex. I often find weirdly contradictory passages like these in traveller's accounts. I end up spending lots of time trying to work out if the 'negative capability' is their perception or mine!

Delete