It seems there is much for us to

question in these modern times. Not least with the recent turn of events – with

the on-going conflicts in Syria and Iraq, and with the humanitarian crisis this

has precipitated in Europe; with the divisive issue of Brexit; with the outcome

of the US Presidential election. But one thing which I never anticipated I’d

ever need to question is a simple act of remembrance.

Each year on this day, November 11th

– Armistice Day, we come together to remember those who have fallen in the two

World Wars of the last century. For as long as I can recall, like so many

people in the UK, at this time of year I have always worn a little red paper

poppy. I learnt long ago when I was a child at school that these commemorative

poppies were made by the smart red-coated Chelsea Pensioners, veterans of these

two wars, and that we wore these poppies as a quiet symbol of our respect and

remembrance for the sacrifices their two generations made to ensure that Europe

and the wider world remained free from the forces of fascism and oppression. As

I grew older and studied this history in greater depth I came to realise that

the global truth – both then and now – isn’t quite so simple as that, but in

essence I always felt that the sentiment behind this day of remembrance was

exactly that simple. War is bad. Never again.

Yet, in recent years I’ve begun to

feel increasingly conflicted about the simple act of donning my paper poppy. It

seems increasingly clear to me that the nature of this act and what it is seen

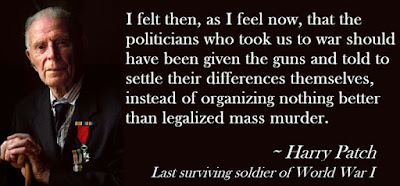

and held collectively to express has altered. With the death of Harry Patch,

the last of those veterans of the First World War in the UK has passed. That

conflict has ceased to be a living memory, it is now history proper. And there

are fewer veterans of the Second World War each year standing in solemn

remembrance at the cenotaph and at local war memorials across the country. But

so too, very sadly, in recent years the numbers of this country’s war dead have

increased significantly with the UK’s involvement in armed confrontations in

Afghanistan and the Middle East. It’s perhaps no surprise then that the efforts

of the British Legion (who organise the annual event of distributing these

paper poppies), and the rise of the charity Help for Heroes, have each sought

to reorient this annual act of remembrance. It’s wholly right and

understandable that such individuals should not be forgotten, but to me

something does seem deeply amiss in all this.

|

| Wartime Prime Minister, Sir Winston Churchill has recently replaced social reformer and Quaker, Elizabeth Fry as the face on the new £5 note |

Armistice Day, in my mind,

represents that ideal of ‘Never Again.’ Yet the evidence of recent years runs

contrary to this. Instead we live in a world where ‘Again and Again’ is

becoming the norm. Armed conflicts are seemingly becoming normalised. War is

big business. Especially for certain members of the elite; politically and

economically, we are told, both tacitly and overtly, that arms are necessary,

wars are necessary. I reject that notion completely. And I increasingly feel

that it is the entire global system which is at fault here.

I am of the generation who came of age as the Berlin Wall came down. For us the end of the Cold War seemed to

herald a new and unprecedented age of freedom, of happiness and contentment to

come. Looking back though, particularly since the UK referendum on its membership of the European Union, I find the seeds of doubt were blindingly

obvious even then. I didn’t understand the desperately bloody events in Balkans

during the 1990s; they seemed to run counter to this Post-Cold War sense of

optimism for the future. They seemed like an anomaly at the time, but since the

Brexit decision I have revisited this era. I immediately turned to Timothy

Garton Ash’s History of the Present (Penguin,

2000) in an effort to help me try to fathom why this idealism and optimism upon

which I’d founded my world outlook now seemed so precarious. The Balkan

conflict was a complex one, but essentially perhaps not altogether too

complicated to comprehend. At risk of being too simplistically reductive it

strikes me as a war of petty prejudices driven by equally petty and tawdry

nationalisms. And this is what now worries me most about the future trend of

global affairs. Populist nationalism is clearly on the rise. In this respect

Timothy Garton Ash is still writing and trying to make sense of our times, even

today (see here). This virulently populist nationalism has become alarmingly

manifest in many countries besides my own. This poses urgent questions for all

of us. What will become of all this? Where are we heading? … Another prescient

book to read in this respect might be Sebastian Haffner’s Defying Hitler (Picador, 2003).

The other day, whilst on my way to

work I was directly accosted by a young man smartly dressed in an expensive

looking suit. He thrust a collection tin at me. In his other hand was a box

filled with paper poppies, poppy wristbands, enamel poppy badges, sparkling "blingy" poppies, and red rosette-style woolly-crocheted poppies.

His manner was volubly direct and aggressive: “Can I interest you in a poppy, Sir?”

His tone was an odd mix of accusatory but needy solicitation. He’d evidently homed

in on me because I wasn’t wearing a poppy already. And he had deliberately

moved to block my path. These actions prompted a similarly forthright reaction

in me: “No.” I said firmly. That reaction I realised was instinctively

reflexive, but nonetheless deeply rooted. I often feel myself harden to direct

confrontation. I tend to stand my ground. But my reply, I realised was in fact the

informed culmination of several years of carefully weighed consideration. As

he’d effectively stopped me dead in my tracks I took a moment and looked around

me. There were many young men similarly smartly dressed like him, squads of

them in fact, all swarming around the entrance to the Tube station I was trying

to enter. I pass by this way every day and invariably there are two men sitting

on the pavement here, with little cardboard signs set before them stating that

they are ex-paratroopers, begging for loose change. They weren’t there that

morning.

A similar thing happened to me last

year too. As I exited Temple Tube station and turned left, where there is a

steep set of stone steps leading up to the street. That day the top of these

steps were lined by a solid wall of military personnel – from the Army, the

RAF, the Navy – all neatly turned out in their immaculate dress uniforms,

looking down on us. Ready. All set to accost (or confront?) this beetling swarm

of commuters exiting the station. This towering wall of military men was almost

impassable. They deliberately didn’t make it easy for the ordinary people to

get by. It’s this imposing blockade of patriotic coercion, intimidating and

expectant which bothers me. How could anyone not want to donate and take a poppy? How could anyone question something which was their duty? Our duty to remember. Our duty to support the … the what?

… The veterans? The British Legion? The national institution of the country’s

armed forces? The lads in uniform? Or the foreign policies of our political

classes and our ruling elite (seemingly regardless as to what their political

colour outwardly professes to be)? There’s an oddly misplaced and uncomfortably

bitter irony in talk of the “Poppy Fascists.”

My cynicism is growing deeper.

Reading how the major arms manufacturers are cashing in on Remembrance Day (see

here) only calcifies my distrust. Reading how many of today’s veterans also

reject this present state of affairs with increasing vehemence (see here) only

compounds my sense of dismay and despair. Something feels very wrong in all

this. And as a historian it is impossible not to anguish and reflect on these

conflicted issues and instincts over and over inside. Not least with all the

centenary events to commemorate that first cataclysmic global conflict, the

first industrially mechanised orchestration of death which swept away so many

young lives, which are happening at present. Those “lions lead by donkeys.” We

flood the moat of the Tower of London with a patriotic efflorescence of our

collective piety. Never again! – And yet … our political leaders green light

the renewal of something darkly awful like Trident – because “it will be good for industry, good for the country’s

economy, as well as for our national security and defence.” They are doing it for us. But how many of them or us

reflect on the fact that one single Trident missile armed with substantially

less than its full capacity of warheads is sufficient to kill more individual

lives than the entire total of those deaths which that moat of blood red poppies

was set up to represent? … That’s more than 888,000 people with just one

missile (see here for a fuller explanation of the maths). It seems to me that

if there are lessons to be learned from history, from war, and from the present

uncertainties in which we live – we’d do well to remember and reflect a little

more deeply.

References:

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments do not appear immediately as they are read & reviewed to prevent spam.