I’ve only read three books by

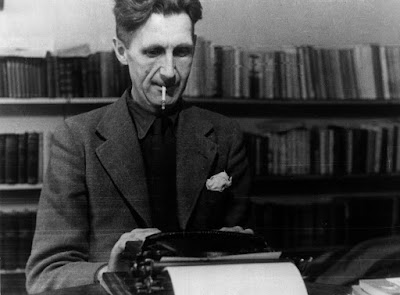

George Orwell, and they’re not the three most people probably associate with

his name. He is, perhaps like Shakespeare, one of those writers whom we somehow

simply know and can even quote

without ever actually having read. I’m not entirely sure if that is a good

thing or a bad thing, but it certainly is a thing.

I may well have read a passage or

two from Animal Farm (1945) in

English classes at High School, but I’ve never read it all. Nor have I read Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949). But somehow

I can’t seem to recall my ever not

knowing about this satirical tale of animals as political allegory for

Stalinist dictatorship. All animals are

equal but some animals are more equal than others. Likewise the “newspeak”, “doublethink”,

“thoughtcrime”, and “Room 101” of Nineteen

Eighty-Four. Big brother is watching

you. But thinking about Orwell recently I was struck by the realisation

that I’d never really engaged with his works. What seemed strange to me is how

in many ways, and considering what little I know of him and his life, he would

most fundamentally seem to be my kind of

writer. As a Sixth Form and then undergraduate

student in my late teens and early twenties I avidly read the political

writings of Mahatma Gandhi, Albert Camus, Vaclav Havel, and later, Aung San Suu Kyi. I also read the

complete short fiction and personal writings of Franz Kafka. But not so much of

Orwell.

The first book of his I read was Down and Out in Paris and London (1933). For a time I contemplated writing my undergraduate

anthropology dissertation on some vague aspect or other of homelessness in

London society. When not in lectures I often idly drifted about London and occasionally

found myself engaging in conversations with various ‘down and outs’ I met on

the streets. But nothing came of it, perhaps because I realised to do such a

study properly would take more time and greater immersion than would be

possible in the timeframe required of an undergraduate dissertation project

(plus, asides from the question of what might be the most appropriate methodology; how to ethically

reconcile oneself with pursuing “participant observation” of such a topic, as

was required of the dissertation module? Should one pose as homeless in pursuit of veracity by being dishonest, or should one be open about being an academic observer, thereby maintaining honesty but creating a barrier through distance?).

In many ways I now regret not doing

that project, comparing Orwell’s observations of London’s homeless with my own

of some fifty-odd years later might have been a worthwhile endeavour. But my

head was probably too much in the clouds at the time, I doubt I’d have been

organised or disciplined enough to have done it justice. Instead I gravitated

onto his novel, Keep the Aspidistra

Flying (1936), which chimed more

with my own somewhat lazy artistic counter-culture inclinations – the story of

Gordon Comstock, a not-very-good poet nurturing a slowly simmering rancour

against the world and society in particular, which resulted in his busily being

determined to go nowhere with his life. A kind of über-Romantic anti-Romantic. But happily, that didn’t last quite

as long as it felt like it did at the time. Life eventually moved on.

And as life moved on, so too I

seemed to leave Orwell behind. It’s only recently that I came back to him. This

time drawn by an interest in his anti-imperialist writings which I thought

might chime with elements of my current PhD research. But there again, how was

it that I already seemed preternaturally aware of his essay, Shooting an Elephant (1936). Racking my

brains I have no recall of how, when, or where I first became aware of this

remarkable piece of writing. Somehow, I just knew about it already.

Hence I bought a copy of his Essays (2014). A gorgeously produced Penguin paperback with a design that harked

back to the iconic 1940s-look of that publishing brand. Rather suitably, I

thought. But inside the text has been reduced to fit this pocket-sized format,

which means that trying to read the thing is rather like trying to decipher the

semaphore of an ant attempting to communicate by dancing across a narrow blank

page with inky feet. However, that screwed-up-eyes intensity of reading repays

the effort well. I found Orwell just as engaging, if not moreso even, than I

did when I was half the age I am today.

I realise now the main thing I

like about his writing, asides from my sympathies with some of his viewpoints

and shared interests in certain topics, is how clear and frank he is – without

necessarily being simply clear and

frank. It’s hard to explain what I mean by this, and that’s perhaps why he’s

such a master prose-stylist. He does it so effortlessly. Although, I bet he did

and didn’t. I bet he laboured long over some parts whilst others must have just

poured out and seemingly wrote themselves. Maybe this is why he seems oddly

timeless. While he might be writing about times and realities which have long

since gone and which in many ways set his writings firmly in the context of

their times – he writes of pounds, shillings, and pence; his weights and

measures are imperial, he writes about drinking pints of mild, and buying so many

ounces of tobacco, to point to the simplest of examples – he also writes very

plainly about some topics which seem oddly open and thereby counter to my

preconceptions of the era; take sex for instance, he can be remarkably candid

about that – although, thankfully, not too

candid.

The social and moral observations

he makes and his analysis of such matters are what perhaps resonate most with the

modern reader, even now. It’s amazing he remains so fresh and seemingly

current, but then maybe he has simply hit on the most unchanging elements of our

reality. Perhaps the world, as he sees and understands it, was ever thus. Like Ben

Jonson’s famous summation of William Shakespeare, perhaps George Orwell is not

so much a man of his time, but rather more a

man for all time – or, to thieve a different aphorism (from Zhou Enlai), is

it still too early yet to tell?

A selection of BBC Radio 4 Programmes exploring the themes and political context of George Orwell's ideas and his writings

I had a very similar feeling about Shooting an Elephant - when did I first read this? Because when I read it recently it felt like I had always read it.

ReplyDeleteWriters like Orwell or Shakespeare simply seem to be part of our national and cultural collective consciousness without having to actively read them. With Orwell though he draws in so much modern history. I also seem to inadvertently keep coming across him, whether it be in a pub in Fitzroy or walking Jura, the remote Scottish island where he wrote 1984. In fact the writing of 1984 is almost as fascinating as the book itself, and inspired me to write a short story about a bunch of characters interacting on Jura that included Orwell and the KLF. The story should probably continue to keep gathering digital dust (ha!) but it was fascinating looking into the life of Orwell on Jura for it.

Sounds like an interesting story!

ReplyDeleteI definitely want to track down a good biography of Orwell now. The essays are a fascinating read, hence he's someone I feel I really should know more about.