Last summer whilst on holiday in

Cornwall I set myself a challenge – to walk from the old fishing

village of Mousehole to the ancient site of Carn Euny in Penwith. This is

familiar ground for me as my family have been holidaying regularly in this part

of Cornwall for several generations. Every summer, whilst growing up, was spent

exploring the coastal footpaths, coves, and villages around Land’s End. In my

early teens my brother and I would hire mountain bikes, and, armed with an Ordnance Survey map, we’d spend a day or two cycling around from one monument to the

next – visiting well known landmarks, such as ruined tin mines and stone

circles, or picking lesser known sites which were simply marked as ‘tumuli’ on the map, intrigued as to

what they might be, hoping to see if anything was still visible at these spots.

Cornwall is littered with prehistoric sites, and so, for me, spending our

summers there was an ideal way to nurture my growing archaeological interests.

So whilst this was familiar ground, having visited Carn Euny several times as a

child, this was the first time I’d decided to walk there; but the real challenge

I’d set myself was to get there using as few roads as possible, sticking as

best I could to footpaths. The other part of the challenge was to incorporate

as many points of historical interest along the route as I could manage.

Last summer whilst on holiday in

Cornwall I set myself a challenge – to walk from the old fishing

village of Mousehole to the ancient site of Carn Euny in Penwith. This is

familiar ground for me as my family have been holidaying regularly in this part

of Cornwall for several generations. Every summer, whilst growing up, was spent

exploring the coastal footpaths, coves, and villages around Land’s End. In my

early teens my brother and I would hire mountain bikes, and, armed with an Ordnance Survey map, we’d spend a day or two cycling around from one monument to the

next – visiting well known landmarks, such as ruined tin mines and stone

circles, or picking lesser known sites which were simply marked as ‘tumuli’ on the map, intrigued as to

what they might be, hoping to see if anything was still visible at these spots.

Cornwall is littered with prehistoric sites, and so, for me, spending our

summers there was an ideal way to nurture my growing archaeological interests.

So whilst this was familiar ground, having visited Carn Euny several times as a

child, this was the first time I’d decided to walk there; but the real challenge

I’d set myself was to get there using as few roads as possible, sticking as

best I could to footpaths. The other part of the challenge was to incorporate

as many points of historical interest along the route as I could manage.

The first place of interest I

passed through was the village of Paul, which is a short walk up a steep lane

from Mousehole. Strictly speaking I could have done this stretch of the route

using a footpath which runs through a place called Trevithal, but this would

have meant missing the village of Paul where there are a couple of notable points of historical

interest. First, on the road up to Paul there are two stone crosses, one on the

approach to the village and the other set in the wall surrounding the Parish Church, which according to Cornish folklore mark the places where early

Christian sermons were preached, converting the local population and thereby ‘saving

heathen souls’ – also, if you keep an eye out and the dry stone walls lining

the road up the hill aren’t too overgrown, at various points along the way you

can make out some names and dates (mostly 19th century) carved into

the stones. At the top of this lane is the Church of Saint Pol de Leon. Its

tower dates back to the 15th century, but the church itself was

largely rebuilt after the villages of Mousehole, Paul, and nearby Newlyn, were

attacked in 1595 by Spanish raiders. Inside the church, some of the pillars still bear the scorch marks from the Spanish raid, and high on one of the

walls near to the stone pulpit is a monument to William Godolphin (died 1689),

whose family fought the Spanish raiders – the monument is adorned with a

Spanish metal breastplate and two swords said to date from the 1550s. Next to

this is a granite and glass monument to the crew of the lifeboat Solomon Browne, which was tragically lost

with all hands in December 1981 whilst attempting to save the crew of the Union Star. The two vessels were wrecked

in extremely bad weather on the rugged coast west of the nearby village of

Lamorna. Outside the church, set in the wall surrounding the churchyard, there

is a monument to Dolly Pentreath (died 1777), who is thought to have been the

last native Cornish speaker (before the language was revived in the early 20th

century). The monument was erected in the 19th century by the

linguist, Louis-Lucien Bonaparte (1813-1891), a nephew of Napoleon I.

Heading west out of the village I

took a footpath which runs alongside the new cemetery and then along a

bridleway which eventually emerges by a stone barn on the road just north of

the village of Sheffield. Here a very short dog-leg along the road gets you

back onto a long footpath through the fields all the way to Kerris. The

hedgerows were all teeming with ripe blackberries which soon stained my

fingertips black and purple as I couldn’t help pausing to pick and eat them as

I went. In one field I was greeted at the far end by a friendly group of horses

who must have been disappointed I’d not come bearing sugar lumps, but still they

happily let me rub their noses all the same. Hopping over the granite stiles in

the hedge-banks I pressed onwards, through a wonderfully mossy, wooded dell up

to Bojewan’s Farm, where I came upon a buzzard with very brown plumage and

yellow feet, perched very close up on a nearby fence post. We looked at each

other quizzically for what seemed like a very leisurely stretch of time before

the bird lost interest and lifted off, almost effortlessly sweeping low over

the field and away with its giant wings outstretched. Throughout the course of

the day’s walk I often heard the distinctive calls of these very majestic birds

echoing across the fields.

Passing through another farm I soon

found myself confronted with a second rather Withnail-esque dilemma. The footpath I needed to follow ran through

a field in which I could hear the distinct sound of a large bull bellowing both

loudly and often. Needless to say – I continued along the track, heading deeper

into the field system (which wasn’t very clearly marked on the map), hoping to

find another way through. As I stood contemplating my rather battered old

Ordnance Survey map I heard the sound of a tractor coming closer. It roared

past me, then rolled back and stopped. The back window opened and the driver

shouted ‘hello’ over the rattling engine, ‘where are you trying to get to?’

‘The Blind Fiddler,’ I replied.

He put the brake

on, cut the engine, and hopped down from the cab.

‘You’ve missed the path back there,

but you probably don’t want to go that way as the bull’s out in that field,’ he chuckled.

And, as if on cue, the bull

bellowed across the hedgerows.

Leaning on the gate we pored over

the map together.

‘What you need to do,’ the farmer

advised, ‘is cut across this field, then go up through “boot field” (See, we

call it that because it’s shaped like a boot!); and then hop over the gate at the

other end.’

I followed his finger as he traced

the route over the map. It was a short cut I’d never have dared taken without

permission.

After a bit more of a chat,

swapping family histories, he opened the gate up to let me through and wished

me well on my way as I set off across the long grassy meadow.

The Blind Fiddler is a standing

stone well worth seeing. It’s tucked away inside a high walled field, and,

though an ‘A road’ passes right by it, you’d be hard pressed to know it was

there hurtling past in a car. It’s a megalith

worthy of the name. A huge grey stone set upright and covered in turquoise

lichen. Its slightly tapered tip is scored with deep striations which only

serve to accentuate its ancient aspect, it seems to stand like a timeless

sentinel. It really is a beautiful thing to behold. Stones such as this one are

also known as menhirs, a term which

derives from the Cornish words ‘men’ meaning stone and ‘hyr’ meaning long – ‘long

stones’. Their original purpose or function is now unknown – they may have had

a religious or ritual significance, or perhaps been boundary or way markers of

some sort. Looking back at the Blind Fiddler’s location from afar it does seem

to be situated at the apex of two distinct valleys which head down to the coast

– but this is simply my speculation made from a single vantage point; perhaps a

survey of the area, looking from a different angle, another interpretation

could just as easily be read into its placing. Its name, ‘the Blind Fiddler’, is a modern appellation, perhaps attributed sometime around the 18th century, after local folklore which claimed that the menhir was a musician who had been turned to stone as a punishment for the sin of playing music on the Sabbath.

Continuing on from here I threaded

my way along footpaths through various wooded gullies and a series of open

fields until I reached a gate into what should have been a final field, at the

other end of which the path was meant to emerge onto a narrow lane. But the

field had recently been ploughed, and so rather than slog through the mud I

skirted the outer edge of the field until I reached the point where the path

was meant to end, only here there was no gate or stile to be seen – just a

solid, overgrown bank which was taller than me. As I paused pondering what to

do I became aware of a second tractor that day which was – this time rather more

purposefully – heading my way. I wondered if I was in for an ear-bashing (or

worse) as this tractor was clearly thundering across two fields at quite some

pace in order to reach me, but – ever the optimist – as the door swung open and

I was hailed with the question: ‘Can I kindly ask what your business is being in this

field?’

I dug out my map, stepped boldly

forward with a cheery smile and asked for the farmer’s help. Pointing out the

footpath and querying whether or not I’d gone astray he sat back and marvelled: ‘You

know, I don’t think anyone’s walked this path in over fifteen years!’

Apparently ‘they’ (the local

ramblers association or County Council, he’d didn’t specify) used to come and

keep the stile – which was a high, stone-tiered sort – clear, but no one had

done this in over a decade and so the route had fallen out of use. As with the

previous helpful farmer he asked me where I was heading and we got chatting

about the ancient monuments dotted round about. The Blind Fiddler was on his

land, although his son now ran the farm. He then very cheerfully pointed me on

my way through two more long fields of dry stubble to a point where I could hop

over a gate through the high bank into the lane. As he roared off across the

field and went back to work I trudged on after him. Some while later, when

I finally reached and successfully summitted the five-bar gate, I paused a

moment and looked back across the field. Down the long slope I watched the

tractor turn and begin to head back up the incline on another lap up the length

of the field and I waved. I could see him waving back from inside his cab with

a smile.

From here on I followed the empty lane up to the village of Brane, where a short walk up a stony footpath

brought me to my final goal: Carn Euny.

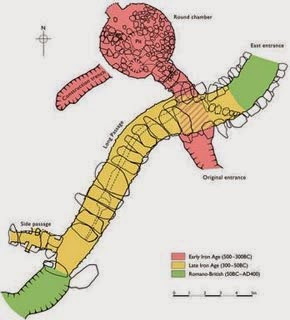

Carn Euny is the site of an Iron

Age village. Prospecting tin miners in the 19th century happened

across an ancient feature here which is known locally as a fogou – Cornish for ‘cave’ – although these features are always

man-made rather than natural. They are long subterranean passageways, either hollowed

out of the natural bedrock or trenches dug and covered with large stone lintels

(in other parts of Europe these kind of features are usually referred to as souterrains). It’s not known what their

original purpose was, but theories suggest they were either used for storage or

as places of refuge, or, as some prefer to conjecture, they perhaps served some

sort of religious purpose (my own opinion is that they maybe served some

combination of all these suggestions at different times). The fogou at Carn Euny is unique though

because it is connected to a circular subterranean chamber with a corbelled

roof, rather like a ‘bee-hive tomb’. Notably the walls of the fogou passageway and the underground

chamber are each footed with courses of smaller rocks which increase in size

with height – a feature which adds an oppressive sense of weight when you enter

inside. Beneath the flagstone flooring of the fogou archaeologists excavating in the 1960s-1970s discovered

fragments of pottery which, dating to around 400 b.c., were stamped with decoration

marks that seem to link the site to similar ceramic types of the early La Tène period found across the

English Channel in Brittany. Other archaeological evidence from the site (pot

sherds, a glass bead, and Carbon 14 samples taken from charcoal remains) indicate

that Carn Euny was occupied from pre-Roman Conquest times, and was eventually

abandoned towards the end of the Roman period.

The layout of the village takes

a very curious form, consisting of courtyard houses laid out in the pattern of

interlocking circles. The low stone walls of these compounds can still clearly

be seen and explored. The roof of the circular underground chamber has recently

been repaired and made safe with a concrete cap and a metal grill allowing

light in from above, creating a bald spot which rather detracts from the view

above ground, but doesn’t impinge too much when you are inside. Opposite the

doorway into the underground chamber there is a small niche, which looks rather

like a fireplace without a flue. The niche backs onto natural bedrock and the

archaeologists who excavated in the 1960s-1970s (led by Patricia M. Christie)

speculated that this might have had some sort of ritual significance, linking

it perhaps to some sort of earth god or goddess worship. It’s unlikely though

that we’ll ever really know for certain what purpose or function this structure

served – but in many ways this only adds to the mystery and the allure of such

ancient sites, each visitor today can simply take their own time to sit inside

and contemplate what they might have seen if they’d sat there some 2500 years

ago.

Read more on the etymology of Carn Euny, by Tim Hannigan | 26 Places in Cornwall

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments do not appear immediately as they are read & reviewed to prevent spam.