It took three years to build the Vasa. Employing a diverse array of craftsmen – carpenters, smiths, ropemakers, sailmakers, glaziers, painters, specialist woodcarvers, amongst many, who laboured to construct the new flagship of the Swedish Royal Navy. Around a thousand oak trees were felled and shaped into the timbers from which her hull was constructed. Her masts rose more than fifty metres over her decks, and hundreds of ornately carved sculptures, all either gilded or richly painted, festooned the ship’s superstructure, making the Vasa a magnificent sight to behold.

She was officially launched on August 10th, 1628. Her maiden voyage was meant to be a special one, marked with great pomp and ceremony. She was manned by around a hundred crew members, who had been given permission on this special occasion to bring on-board their wives and children. The ship was initially kedged (hauled by means of a small anchor) from her berth on the quay below the Royal Tre Kronor Castle out into Stockholm harbour where a light wind was blowing. Here the sailors climbed the rigging and unfurled her sails for the first time. Setting her foresail, foretop, maintop, and mizzen as, Söfring Hansson, her Captain, had ordered, she began to move across the harbour. Her guns fired a salute. After a distance of just 1,300 metres she encountered a stronger wind which caused her to heel to one side, as the angle of incline continued to increase her open gun ports swiftly listed below the waterline. As one contemporary report described, the “water gushed in through the gun ports until she slowly went to the bottom under sail, pennants and all.”

It’s thought that some fifty people

died in the disaster. Captain Hansson was imprisoned, but he was eventually

released after an official inquiry found that no one could be held responsible

for the sinking. Hansson and the crew all testified that no operational mistakes

were made on-board, the ship was fully loaded with ballast, and all the guns

were properly lashed in place. Everyone seemed to agree the fault lay in the

ship’s construction. She was top heavy. Her keel was too small in relation to

the size of her hull, her rigging, and the weight and positioning of her

artillery. The Shipmaster had tested the stability of the ship when she was

moored at the quay. Thirty men had run in unison back and forth across her deck.

They’d stopped when after only three runs it was feared she’d roll over. An

Admiral of the fleet, Klas Fleming, had been present at the test, but his only

comment seems to have been a troubled sigh: “If only His

Majesty were at home!”

King Gustavus II Adolphus was

anxious to acquire a powerful new ship such as the Vasa for his Navy as quickly

as possible, and so, whilst away in Prussia engaged in a war with Poland,

fighting against his cousin, Sigismund (who had been deposed from the Swedish

throne in 1599), the King had approved the ship’s design. But ultimately, while

the blame for the disaster would seem to put a number of individuals at fault –

with the King himself, the shipbuilder, Henrik Hybertsson (who had died the

previous year), and Admiral Fleming, perhaps the foremost among those seemingly

culpable, the actual cause was essentially the ‘defective theoretical know-how’

of the period. Simply put, the Vasa

was hitherto an untried experiment in shipbuilding and in design. Circumstances

and protocols colluded to propel the project on even when doubts were becoming

apparent, and so the proof of her seaworthiness only came with the unfortunate first

unfurling of her sails.

The Vasa’s maiden voyage may have only been a short one, in which she

never even left the waters of her native harbour, but it was more of a historic

journey than any of the many observers crowding the harbour that day, or any of

those on-board, could possibly have imagined. When she sank off Beckholmen

Island she settled near enough upright on the seabed. Consequently some attempt

was made soon after to raise her, yet the task proved too difficult. A diving

bell was used to salvage the majority of her guns, after which she was pretty

much forgotten about until 1953. A man named Anders Franzen began a search in

the local archives, poring over accounts of her sinking, attempting to locate

the site of the wreck, he later moved his search to the waters around

Beckholmen, carrying out dragging and sounding operations until he had narrowed

the search area. Subsequent dives confirmed he had found the ship lying at a

depth of 32 metres. This depth was practically perfect. It meant the Vasa was deep enough to have remained

largely unharmed by other vessels passing over her, yet not too deep to cause

great problems for a modern day salvage operation. This, plus the cold

temperature and low salinity of the seawater of Stockholm harbour, meant she

was exceptionally well preserved.

With the assistance of the Swedish Navy, Franzen lead a team who worked together to dig a number of tunnels beneath the Vasa’s hull, through which thick steel cables were threaded. The operation which began in 1957 culminated on April 24th 1961 when the timbers of the Vasa broke the surface of the water. The divers had worked long and hard on the seabed to shore up the near intact hull of the ship, such that once she had been raised they began to pump the water from her and eventually she floated by herself. It was a remarkable feat, and, even moreso, it is still quite amazing to watch film footage of the Vasa moving by herself, floating on her own keel once again, as she drifted into a dry-dock on Beckholmen Island, 333 years after her fateful maiden voyage. The Vasa really is a ship which has sailed through time.

I forget when I first saw

photographs of the Vasa, perhaps only

a couple of years ago, but I do remember I was instantly agog at the exceptional

state of her preservation. I was six years old when the Mary Rose was raised from the waters of the Solent on October 11th

1982. I remember the excitement of seeing the first timbers breaking the

surface live on television that morning before going to school, but I think I

was probably expecting a more intact spectacle of a sunken galleon, something more

like that of the Vasa, in fact!

However, a few years later I was more than suitably impressed when I saw the

large section of the Mary Rose’s hull

being sprayed with preservatives where it was being conserved in Portsmouth

(I’ve yet to re-visit and see the new Mary Rose Museum which opened on May 31st

2013). So the fascination of seeing such an old ship brought to the surface certainly

caught my imagination very early on, hence having seen photographs of the Vasa I was instantly itching to see her for

real. Earlier this year that itching transferred to my feet and could no longer

be ignored, so I booked myself a plane ticket to Stockholm. I spent an entire

day at the Vasamuseet – absolutely absorbed, exploring every aspect of the

displays and marvelling at the magnificent ship itself, which is now almost

entirely restored – nearly 98% of the ship is original!

Your first sight of the Vasa as you enter the vast museum hall

is truly breathtaking. I couldn’t help thinking of the scene towards the end of

the 1980s children’s adventure movie, The Goonies, when the children suddenly see the old pirate ship hidden in the

sea cave for the first time! The Vasa sits

in a converted dry dock and the different levels of the vast hall enable you to

walk around the ship and examine her structure and ornate decorations up close.

She is still too fragile to allow visitors to go on board, but as the work to

conserve her (the largest current task being to replace each of her now

corroding metal bolts) is still on-going, it’s sometimes possible to see the

conservators and engineers on-board at work. A multi-lingual film plays in an

auditorium near the entrance which tells the story of her construction, launch,

sinking, salvage, and conservation in vivid detail.

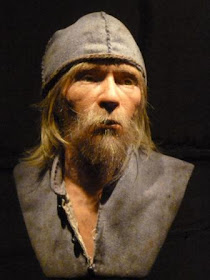

A number of models and full-size reconstructions help to explain each part of the ship as well as how she was raised, and a number of guides give frequent introductory tours. The floor directly beneath the ship’s hull, plus another floor higher up, each display an incredible array of archaeological finds which were recovered from the ship and the seabed surrounding her wreck site, including a number of skeletons of the crew and guests who were on-board and lost their lives when the Vasa sank. Some of these were found still wearing their clothes which had been almost perfectly preserved in the rich silt which had filled the ship’s hull on the seabed. The unusual fact that women and children had been allowed on-board in addition to her normally all male crew has meant that the Vasa has yielded a wealth of archaeological information encompassing all of 17th Century Swedish society.

A number of models and full-size reconstructions help to explain each part of the ship as well as how she was raised, and a number of guides give frequent introductory tours. The floor directly beneath the ship’s hull, plus another floor higher up, each display an incredible array of archaeological finds which were recovered from the ship and the seabed surrounding her wreck site, including a number of skeletons of the crew and guests who were on-board and lost their lives when the Vasa sank. Some of these were found still wearing their clothes which had been almost perfectly preserved in the rich silt which had filled the ship’s hull on the seabed. The unusual fact that women and children had been allowed on-board in addition to her normally all male crew has meant that the Vasa has yielded a wealth of archaeological information encompassing all of 17th Century Swedish society.

Stockholm itself is still very much

a seafaring city. Strolling about the quays of the many little islands which

make up the capital I saw a number of resident tall ships and vintage steamers.

On Beckholmen, the dry-dock where the Vasa

was first brought after she was raised and re-floated is still in operation. The

buildings, churches, and cobbled lanes of Gamla Stan, the old town, are full of character,

and not far from the Vasamuseet itself is a vast park, the Djurgården, large enough to get lost in – which

provides a wonderful green escape from the bustle of the city. A visit to the

Swedish History Museum is also a must for any history buff visiting Stockholm,

as it houses an excellent collection of art and artefacts from the many varied

periods of Sweden’s long history – not least that of the Vikings.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments do not appear immediately as they are read & reviewed to prevent spam.