Part

V

“The

morning of the 10th [August 1924] broke fine; and about 9 o’clock we joined the happy throng that

wandered leisurely out of town and up alongside the mountain torrent to Dorje

Drag. The level sward in front of the lamasery was already covered with tents,

the Tibetans being quite unable to resist the idea of a picnic; and the

brightly striped canvas and gaily coloured clothes of men and women made a

pretty picture against the rows of sombre poplars in the background. As we made

our way through the crowd, now and then one more polite than his neighbours

would stand aside, bow with out-stretched hands, and protrude a tongue of

monstrous size and usually healthy colour, the polite form of salutation in

Tibet. […] Passing through the

vestibule with its great Mani drums, revolved by devotees as they go by, and

entering the courtyard, we saw stretched opposite us, concealing the entrance

to the main temple, an enormous painting on cloth of Dedma Sambhava.” (G. A.

Combe, H.B.M. Consul at Chengtu).

Almost 86 years to the day, on

August 7th 2010, I walked through the vestibule described above into

the same Gompa – Dorje Drak in དར་རྩེ་མདོ། Dartsendo (Tachienlu, or Kangding 康定 , as it is

presently known in Chinese). Except I wasn’t greeted by anyone poking their

tongue out at me, nor by the sight of a huge thangka painting unfurled from the roof of the main temple building

to the courtyard floor, instead the Gompa was rather quiet with just a few

monks and local people lolling about or sitting on the grass. It was all very

calm and relaxed. I wandered round, exploring all the temple halls. The place

was filled with prayer wheels, and, in the main hall in front of the image of

Guru Rinpoche (Padmasambhava) I saw a man performing a full set of devotions –

pressing his palms together first over his head, then in front of his forehead,

then in front of his chest before kneeling, and then, leaning forward with his

palms placed on two small squares of cloth which, pushing forward, he would

then use to make himself lie completely flat upon the floor by sliding forward,

his face then flat to the floor, forehead touching the floorboards. He’d then

reverse the procedure to stand up again, before repeating the whole process.

I’ve no idea how many prostrations he made in total, but it was clear that it

was likely to have been many.

Visiting the Tibetan Gompas at

Dartsendo/Kangding was one of the main research objectives of my trip. I’d

managed to thoroughly confuse myself with a range of old and modern photographs

found in Louis King’s private papers as well as those of some of his

contemporaries, along with a multitude of other more up-to-date images, mostly

published on the internet. It was clear that there are three main Gompas in the

town, with other lesser shrines and religious buildings (Taoist and Confucian

too) dotted around the surrounding hillsides. Of these three main Gompas, in

Louis King’s time, there was one situated in the centre of the town – Ngachu

Gompa (Anjue Si) – with two outside the south gate, Dorje Drak Gompa (Jingang

Si) and Lhamotse Gompa (Nanwu Si), which have since been absorbed into the

expanded town (the three town gates are now all long gone).

Ngachu Gompa (Anjue Si), which was under-going massive architectural alterations, 2010

Dorje Drak Gompa (Jingang Si), 2010

Lhamotse Gompa (Nanwu Si), 2010

These last two Gompas

are both situated fairly close to one another, and have apparently been

confused and conflated by commentators from the early 20th century

right up to this very day. Several of the accounts of early Western travellers

through the town wisely remain rather vague, whereas more modern books (even

English language books by Chinese publishers), and an array of websites mix the

two up with bold and confident frequency! (N.B.

– Naturally, not wanting to throw stones too readily, I’d welcome any

comments or corrections on anything I might have inadvertently skewed or got

plain wrong in any of the posts here which make up the glass house of my own

blog!)

And so, having long pored over this

issue with a crossword puzzler’s determination to crack the clues and

definitively complete the conundrum I’m now about to boldly venture my own

theory as to how these mistakes may have arisen! … The root of the problem is

possibly a photograph taken by Joseph Rock published in the National Geographic Magazine in October

1930, or rather – it’s not Rock’s fault (he gets it right), it’s someone’s

misinterpretation of his photo which has gained currency and run like silent,

slow burning wildfire. This is the photograph:

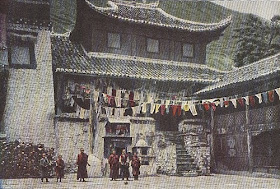

Its original caption reads: Plate XVI – “Prayer flags adorn a shrine of

the yellow sect.”

Joseph Rock’s description of this Gompa

as belonging to the “Yellow Sect” (Gelugpa) indicates that it is most likely

Lhamotse Gompa (Nanwu Si), yet Rock’s photo is frequently reproduced with the

confident assertion that it is Dorje Drak Gompa (Jinggang Si), yet Dorje Drak

in fact belongs to the “Red Sect” (Nyingma). A photograph of the exterior of

Dorje Drak features on the same page with the caption: “Thunderbolt Monastery, a stronghold of the Red Lamas near Tatsienlu”,

hence perhaps the possible origins of this misattribution.

Dorje Drak (left) and Lhamotse (right) Gompas by

Ernest Henry Wilson, 1908.

Similar view of Dorje Drak and Lhamotse Gompas, 2010.

Both Gompas have been heavily

altered since Rock’s time, but a bit of time spent comparing Rock’s image with

those of Ernest Henry Wilson (1908) and Louis Magrath King’s photographs (c.1920-1922) make

the distinction quite clear for me (looking at the roofs of the side

buildings), and even when compared to these two modern views of the same part

of the Gompa in Rock’s photo which I took during my visits to each (the

relative position of the slope of the hillside in the background is one key

indication).

Dorje Drak Gompa

Lhamotse Gompa

“Prayer flags adorn a shrine of

the yellow sect.” (Lhamotse Gompa) by Joseph F. Rock, 1930

Lhamotse Gompa by Ernest Henry Wilson, 1908

Dorje Drak Gompa by Ernest Henry Wilson, 1908

George Combe’s description quoted

at the start of this post is possibly one of the most well known descriptions

of a religious dancing festival held at Dartsendo. Rinchen Lhamo, who was Louis

King’s wife, calls it the ‘Ya-chiu’ or ‘Summer Prayer’ – Combe, however,

euphemistically calls it ‘The Devil Dance.’ Rinchen gently takes issue with

this description: “I do not know why they

should call it so, for it has nothing to do with devils, but is a service of

worship of Heaven, of intercession with Heaven on behalf of the whole people.

It is our equivalent of your Christmas and Easter festivals.

Everybody goes to the Ya-chiu. It is

the principal fête of the whole year, and lasts

three days in succession, taking four or five hours each day from morning to

afternoon. It is held in the court-yard of the Gompa. Awnings are erected on

each side of the entrance to the church-hall. Under them, on each side of the

entrance, sit the priests clad in full sacerdotal robes, amongst them those who

with trumpet, clarionette, cymbal, drum and bell, take the place with us of

your organs and orchestras. The chief officiating priest, the Living Buddha if

there is one in the Gompa, sits on a raised dais under a canopy. The people

occupy points of vantage, such as the balconies, the flat roofs, and the

courtyard itself, in which latter they form a circle linking up the rows of

priests. This circle is the arena where the dancing takes place.”

Louis and Rinchen’s first daughter,

who was born at Dartsendo (Kangding) in 1921, was given the Tibetan name

“Sheradrema (She(s)-rab (s)Gröl-ma)”

by Runtsen Chimbu, the Living Buddha of Dorje Drak. And according to a note

made by Louis this name means ‘transcendent wisdom’ combined with the Tibetan name

of the Goddess of Mercy – Drolma; Tara in Sanskrit, or Kuan Yin in Chinese.

Rinchen was certainly a devout Buddhist, but whether this means she was a

follower of Nyingma Buddhism I’m not entirely sure. I suspect she was, as there

is a picture of a Tibetan priest, a “Ge-she or Doctor of Divinity”, in

Rinchen’s book We Tibetans (1926), to

whom she was related and whom the monks at Dorje Drak seemed to recognise when

I showed them his photograph. But at present it’s hard to know for sure.

Lhamotse Gompa by Louis Magrath King - Then & Now (c.1920 & 2010)

There are a number of photographs

taken by Louis of some kind of festival at Lhamotse Gompa (some look religious in nature, possibly connected to the 'Ya-Chiu', others appear to be traditional Tibetan opera). I’ve seen a similar

set of photographs, presumably of the same events, taken by another of

Louis’s consular colleagues several years later, taken from quite a reserved

distance whereas Louis’s were for the most part taken very much in the thick

of it all (... I suspect he’d have made quite an affable anthropologist had he been

so inclined!). It was remarkable to wander into Lhamotse and spend some time

matching his views from the 1920s with the present day. I was extremely lucky

as I discovered from one of the Lamas, Lobsang Yeshe, that the building works I

had encountered surrounding the Gompa were being undertaken to enlarge the

monks’ living quarters – had I arrived a month later he said, the old living

quarters (which feature so prominently in Louis’s old photographs) would have all been

gone! – Involuntarily I couldn’t help expressing my sadness at this fact, but the

young Lama smiled at me and said very simply: “Nothing lasts forever, everything changes.” I have to admit I was

struck by his words quite deeply, and, with a little amusement, I thought to

myself that if I had climbed these mountains in search of an epiphany – this

was certainly it. Perhaps the ardent pursuit of history (even if it is one’s

own extended family history) is an ultimately futile exercise? … Why cling to

the past?

The building works at Lhamotse Gompa, 2010

Well, maybe not entirely futile as

my trip was certainly more than a mere fact-finding mission, it was in many

ways also an exercise of self-fulfilment in itself. I found a lot more than

just history during this trip. I think the most abiding thing I took away with

me was in fact the kindness of all the people I met. There’s no denying that my

stack of old black and white photos helped prompt smiles and a sense of

connection. Indeed, I spent quite a bit of time over several visits at both

Dorje Drak and Lhamotse, where I was very much welcomed in by the Lamas who

were fascinated by the old photos I’d brought with me. Some of the Lamas spoke

a little English, and, with many of the others who didn’t, we managed to converse

with the aid of some well-thumbed copies of rather antiquated-looking

Tibetan-English dictionaries, which I understood had originally come by way of

India (and which contained some quaintly old fashioned English colloquialisms).

In turn they taught me a few phrases of Tibetan. One monk, named Sonam Topden,

very kindly invited me into his tiny room and introduced me to that famous

Tibetan staple tsamba which I’d often

read about but never before tasted. I made a marvellous mess making it! We

chatted away for quite some time with the help of his old dictionary and he wrote

the name of Lhamotse Gompa in Tibetan for me. He was also quite an accomplished

draughtsman as I saw several beautiful drawings he’d sketched of a seated

bodhisattva – much like one I’d seen carved on a mani stone in another part of the town.

By the time I left Lhamotse that

evening the gates had been closed and the monks were all loudly reciting texts

in the courtyard. I wondered if they were chanting sutras but was told that

this was something more like ‘philosophy’ disputation (?). The monks all smiled

warmly as I passed by, and, as one young monk drew nearby he grinned and whilst

looking at me quietly slipped the word “Demo” (hello) in amongst his recitations.

As I’ve said, the Gompas have all

been architecturally altered or elaborated and expanded over time. Looking at

them it was hard to tell how old some parts were. The living quarters of

Lhamotse clearly matched Louis’s old photos as did the large flagstones of the paved

courtyard, yet the balcony lattice-work had been replaced and the staircases,

as Lobsang Yeshe observed, were no longer quite so steep. I read in a recently

published travel guide that Dorje Drak had been completely destroyed in 1959

(no reason given as to why) and so later rebuilt. A final happy discovery I

made at Dorje Drak related to two old photos of the Gompa’s exterior, one taken

by Louis King and the other by Joseph Rock (as well as another of Ernest Wilson’s

too, if you have a very keen eye) –

which was that there had once been two large chortens or stupas

standing in the open fields just outside the Gompa. They are now both gone, and

the Gompa is today surrounded by houses with little gardens, but when lining up

a modern view of one of Louis’s old photos I noticed a number of mani stones

piled along a garden wall. It was clearly evident that these had been dug up

with the vegetables! They lined the top of the overgrown wall and yet more were

propped alongside a nearby hut. A trace of the old chortens it seemed remains.

I wondered how many of these old mani stones might have been there and

witnessed Louis taking the very same photograph as me some 90 or so years

before?

Dorje Drak by Louis Magrath King, c.1920

Dorje Drak, 2010

“Thunderbolt Monastery, a stronghold of the Red Lamas near Tatsienlu”

Dorje Drak, by Joseph Rock (published 1930)

To be continued … Part VI

References:

“The

Devil Dance at Tachienlu (Dartsendo)” by G. A. Combe in ‘The Journal of the

West China Border Research Society, Vol. II, 1924-1925’ – a more commonly available version of this article can be found in: "A Tibetan on Tibet" by Paul Sherap & George Combe (London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1926)

“We Tibetans” by Rinchen Lhamo (London: Seeley Service Co., 1926)

“The

Glories of Minya Konka” by Joseph F. Rock in ‘The National Geographic Magazine,

Vol. LVIII, No. 4, October 1930’

“Mapping the Tibetan World” edited by Gavin Allright & Atsushi Kanamaru (Tokyo:

Kotan Publishing Inc., 2004)

“Edge of Empires” by Tim Chamberlain in 'The British Museum Magazine, No. 66 (Spring/Summer, 2010)'

“Edge of Empires” by Tim Chamberlain in 'The British Museum Magazine, No. 66 (Spring/Summer, 2010)'

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.JPG)